|

telescopeѲptics.net

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪▪▪▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪ CONTENTS

◄

6.5. Strehl ratio

▐

6.6.1. MTF - aberration compounding, CCD, limitations

► 6.6. MTF - Modulation transfer function

PAGE HIGHLIGHTS Modulation transfer function (MTF) is commonly used to describe the convolution of point spread functions (PSF) and the Gaussian (geometric) image of an object that is a continuous sinusoidal intensity pattern, in effect a continuum of dark and bright lines gradually changing from the maxima (in the middle of the bright line) to minima (middle of the dark line). The convolution integral sums up energy arising from the PSF blotches created at every point of the Gaussian image, and so describes the corresponding diffraction image of the pattern. Changes in the PSF due to aberrations, pupil obstructions and other factors affect the quality of this diffraction image, specifically its contrast level and phase distribution. In general, convolution with the PSF smoothes out, i.e. flattens intensity distribution of the sinusoidal (or any other) pattern, lowering the contrast and acting as a low-pass filter (i.e. imposing limit to resolution) - the larger PSF vs. pattern's frequency, the more so. The MTF is a part of the complex function describing this process, called Optical transfer function (OTF). While OTF is limited to the effect of system PSF on imaging this single form of object - a sinusoidal intensity distribution - it is accepted as a performance indicator for imaging in general. The OTF consists of two components: (1) MTF, and (2) phase-transfer function (PTF). The former is its modulus, or magnitude, expressing the relative change in contrast of the pattern image vs. aberration-free aperture, and the latter quantifies the linear lateral shift of this pattern caused by the change in PSF intensity distribution due to aberration. That intensity distribution change may be radially symmetric (such as draining of the energy from the central maxima with defocus or spherical aberration), or asymmetric, for example due to coma aberration (FIG. 100, middle). The basic relation between OTF, MTF and PTF can be presented as:

OTF = |OTF|e iPTF

= MTFe iPTF

implying that the MTF is the absolute value of the OTF (e

is the natural logarithm base, 2.718; note that the equality is not

present with the commonly used form of the OTF, MTF, which entirely omits the phase factor). Since OTF contains

the imaginary

number i, it is a complex function consisting from the

real and imaginary part, the latter being the part containing the imaginary

number. The imaginary number i=(-1)0.5

is convenient for expressing angular shifts, in this case angular shift of

the sinusoidal MTF intensity pattern phase at a given Gaussian image

point due to the pattern's lateral shift, caused by aberrated PSF. With

eiPTF=cos(PTF)+isin(PTF),

the two parts of OTF function can be expressed as:

OTF = MTF[cos(PTF) + isin(PTF)] = MTFcos(PTF) + MTFisin(PTF),

with the two factors at right being the real and imaginary part of the OTF, respectively (noting that the PSF

is usually annotated as angle). Either can be plotted separately, the

former, being cosine function, originating at 1 for zero spatial

frequency, and the latter originating at zero. If PSF retains any form

of symmetry around a line splitting it in two halves (i.e. symmetry in

its pupil aberration function), the imaginary part vanishes (because in

such case the shift can only be zero or π,

for contrast reversal), and OTF reduces to OTF= MTFcos(PTF).

This is the case with defocus, spherical aberration and astigmatism, for

any orientation of the PSF, and with coma only for a single orientation,

along the axis of aberration. For all other orientations the coma OTF

consists of both, real and imaginary part.

It is important to note that, since eiPTF=cos(PTF)+isin(PTF)

does not represent a sum, rather coordinates of a complex number, the

real part of the OTF does not represent the magnitude of OTF (i.e. MTF),

except when PTF equals zero (no phase shift). If we use the common

notation for the real and imaginary part, Re and Im,

respectively, then the relation between them and the MTF is given by |OTF|= MTF= (Re2+Im2)0.5.

As illustrated below, eiPTF

is not a value, rather phase descriptor. Hence OTF magnitude is not

affected by it.

OTF can also be defined in terms of PSF, as OTF

Or, more directly, just as the

Fourier transform of aberration-free pupil

function

(i.e. Fourier transform of the square pulse) is sinc function, so is the

Fourier transform of triangular function

- which is the form of aberration-free 1-D OTF for square

pupil, with the OTF form for circular pupil being only slightly

different - the sinc

function squared, or PSF. In other words, the PSF is proportional in

form to the continuous spectrum of frequencies contained as a sum of

harmonics in the triangular (or near-triangular) function form.

It is important to note that the OTF relations above are, by their basic concept, valid only for incoherent light. Formal

derivation states that this type of pattern in coherent light would be

reproduced without any distortions in amplitude or phase, i.e. with 100%

contrast transfer, with the sudden drop to zero at the cutoff frequency

2λ/D (coherent transfer

function).

As above relations show, MTF does not

include possible lateral shift of intensity pattern in any way. This is

not by choice, rather by the inherent property of MTF defined as the

modulus (magnitude) of contrast transfer as a function of spatial frequency, with

every spatial frequency treated as an isolated contributor to the

function. Thus, lateral shift of the pattern is no factor, only the

contrast level is recorded. MTF alone shows the efficiency of contrast transfer

from the object to

its image with zero intensity phase shift, for a single orientation in the aberrated image, normally that

along the axis of

aberration. However, 180° (π

radians) phase shift, which can be caused by large amounts of

aberrations, will result in contrast reversal, i.e. switch of

bright and dark areas in the image vs. object. For instance, such image

of F, in addition to it being distorted by the large level

of aberration, could make it unrecognizable, even if contrast needed for

detection is there. Hence, the OTF phase factor is potentially important

factor in predicting image quality, but only in the presence of large

aberrations, well above the level found near axis in optical telescopes

(for instance, contrast reversal due to primary spherical occurs at near

2λ

P-V wavefront error).

Similar to MTF is the contrast transfer function (CTF),

the difference being that the latter describes impulse response (i.e.

contrast change in the image vs. object) based on an object that is a

continuous square wave intensity distribution, in effect a continuum of

bright and dark lines with even intensity distribution over

them.

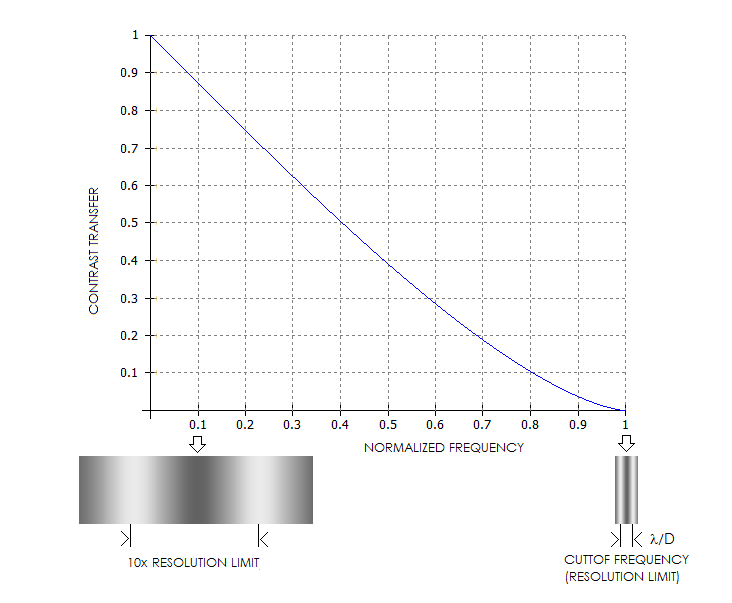

Some additional basic aspects of the OTF/MTF

are given below. INSET A illustrates characteristic form of the MTF,

showing contrast drop as a function of spatial frequency

ν

for brightly illuminated object with high inherent contrast, as well as

the effects of change in illumination/contrast level. For

comparison, graph also shows the CTF. INSET B illustrates the

effect of phase shift, INSET C shows OTF expanded to include

radial PSF dimension and its effect, and INSET D illustrates

polychromatic MTF.

INSET A:

TOP LEFT: Standardized MTF object form

is a continuum of parallel, equally spaced

bright contrasty lines on dark background, with irradiance

modulation defined as infinite sinusoidal distribution. The line width, equaling that

of the dark/light pair, is

inversely proportional to the spatial frequency

ν,

normalized to 1 at the cutoff frequency D/λ cycles per radian (the

inverse of the angular limit to resolution λ/D

in radians, D being the aperture diameter), where image

contrast drops to zero (linear cutoff

frequency is the inverse of the linear limit to resolution

λF,

or 1/λF in lines per mm, for λ in mm). This form of

intensity distribution can be represented as periodic sinusoidal wave,

with the contrast determined by the relative intensity of its maxima

vs. minima. Image of this pattern has the relative intensity and

contrast dampened due to the effect of

diffraction, whether without

or with aberrations present, At any given frequency, MTF is a

ratio of the output (image) to input (object) modulation amplitude.

Mathematically, it is Fourier transform of the system's

PSF (more specifically, it is

an integrated sum of the PSFs for every point over its intensity

distribution profile, i.e. convolution of object's Gaussian image

and aperture's PSF). At

the limit of resolution for aberration-free aperture, the line width

is nearly equal to the aperture's

FWHM.

At right, shown is the effect of 1 wave P-V of

defocus on the image of an object that is not the standard MTF

pattern, but one in which bar width is oriented horizontally, with

the line width changing continuously according to the spatial

frequency. Top image (A) is aberration-free, and bottom (B)

defocused one. If the aberration is large enough - in the case of

defocus ~0.9 wave P-V or larger - image of such object will show

contrast reversal - where bright lines become dark and vice versa - indicated by the OTF, but not the MTF. The reason

was immediately apparent from the PSF intensity distribution for 1

wave of defocus, developing dark circle (minima) at the center of

the pattern. Hence, MTF does provide information on contrast

transfer, but not on the image itself. To reconstruct the image, we

need OTF. This, however. may have significance only with large

aberrations, generally about 1 wave P-V and larger (a few more

examples at ). OTF for smaller aberrations does not fall below zero,

thus there is no contrast reversal to affect image.

For aberration-free clear aperture, the MTF

is given by MTF=(2/π)[cos-1ν-ν(1-ν2)0.5].

It can be also expressed as:

with the angle α

in degrees found from cos(α)=ν

(for software use, the angle obtained from arccos(ν) is in radians,

hence needs to be multiplied with 180/π for degrees; the

corresponding form for the first factor is then 2arccoss(ν)/π).

Graphically, MTF

contrast transfer equals the relative overlapping area of two

identical circles, in units of the circle area (FIG. 62, top

right), with the circle diameter normalized to 1, and the center

separation s=ν

varying from 0 when the circles are coinciding (ν=0),

to 1 when only touching (cutoff frequency ν=1).

Similarly, the normalized MTF for

reduced aperture (still of

unit diameter, with v=0 when the two circles are touching, smaller

inside the larger), equals the overlapping area with the smaller

circle appropriately reduced in diameter, with overlapping area

being in units of the smaller circle area. The actual range of

resolvable frequencies of a smaller aperture is in proportion to the

aperture reduction factor. In terms of MTF, CTF is given as

CTF=(4/π)[MTF

Graph below illustrates normalized frequency implications with

respect to MTF pattern characteristics. Since cutoff frequency

is given in frequency form, as D/λ, the inverse of the actual

resolution, the

lower frequency, the wider pattern. With the resolution at cutoff frequency,

λ/D, being 2.44 times smaller than the angular Airy disc

diameter (given by 2.44λF/f, f being the focal length,

hence equaling 2.44λ/D), the pattern width is proportional

to the inverse of normalized frequency: it is twice wider than at

the cutoff at 0.5 frequency, five times at 0.2 frequency, and so on.

To express it in Airy disc diameters, it only needs to be divided

by 2.44 (so it will be 2/2.44=0.82 Airy disc diameters wide at 0.5

frequency).

It is important to understand that the MTF

graph, such as the one above, does not set absolute values for

the contrast drop, or limit to resolution. Both are strictly applicable only

to the particular MTF object form used for its calculation: a sinusoidal pattern of

bright lines on dark background, λF/2ν

wide linearly, F being the focal ratio f/D (i.e. linear width of

the bright line at resolution limit is

λF/2, or nearly one fifth of Airy

disc diameter). Actual contrast

drop-off and limiting resolution will vary with the specific properties

of details observed, background, and peculiarities of eye perception, or

detector properties. For non-continuous patterns, sinusoidal,

square-wave, or others, contrast transfer will generally increase with

the reduction in the number of lines (FIG.

103).

One example is

the resolution threshold for low-contrast MTF-like planetary details which is,

according to the LCB threshold level in FIG. 100, approximately half

of that for

brightly illuminated contrasty object. Another is a dark line on light

background, which can be detected at an angular width several times smaller

than the angular diffraction resolution limit

for point-images of ~λ/D radians, because it is the

Edge Spread Function,

not the PSF, that is applicable in determining its diffraction intensity

distribution.

An actual object that

comes very close to the standardized MTF scenario is a pair of nearly

equally bright stars at the optimum brightness level. Resolution-wise,

the MTF limiting resolution (cutoff frequency) is nearly identical to the empirical Dawes' limit in double star

observing. However, for pairs farther from the optimum brightness level,

or,

especially, pairs with significant difference in brightness, the resolution

limit is lower, or much lower.

Still, despite the MTF being

standardized to a single object form sample and brightness level, it is considered to be a reliable

general indicator of the effect of wavefront aberrations - or any other

factor affecting wave interference in the focal zone - on image quality.

As mentioned, given relatively low RMS wavefront level of any aberration will result in

near-identical overall contrast loss, but

the specifics will vary somewhat. FIG. 101 illustrates variations in

the aberrated PSF

(left) and MTF (right) for common wavefront aberrations of 1/13.4 and

1/6.7 wave RMS (graphs generated by Aberrator

freeware, Cor Berrevoets).

FIGURE 101: PSF and MTF plots for clear aberration-free aperture

(black), and aberrated (red) at the 0.80 Strehl level, and that

wavefront error doubled.

DEFOCUS: 1/4 and 1/2 wave P-V. Doubling the error halves the peak

PSF intensity (Strehl), but the average contrast loss is three times

greater (20% vs. 60%, given as a ratio number by the differential

between the Strehl and 1). Note that the Strehl for 1/4 wave WFE of

defocus is slightly higher than 0.80.

PRIMARY SPHERICAL ABERRATION: 1/4 wave and 1/2 wave P-V errors have

nearly identical effect on the PSF maximum as with defocus, but the

more widely spread energy causes more of contrast loss at the lower

frequencies, while the smaller central maxima results in somewhat

better transfer at mid-to-high frequencies. The transfer is again

inferior near the cutoff due to the smaller bright core with

defocus. Being close to zero, the cutoff frequency for 1/2 wave P-V

is about 20% lower in field conditions.

PRIMARY ASTIGMATISM: The effect of 0.37 and 0.74

wave P-V is similar to 1/4 and 1/2 wave of defocus in that the

energy spread out of the Airy disc is mostly contained closer to

central maxima, resulting in less of contrast loss at low

frequencies. Unlike defocus, does not change radial symmetry of PSF,

astigmatism gives to it cross-like shape which, similarly to coma's

asymmetry, gives the best contrast transfer when cross orientation

is identical to that of the bars (green) and the worst when it is at

45° angle.

TURNED EDGE: 2.5 waves P-V is needed that turned

edge starting at 95% the radius to lower the Strehl to 0.80. Lost

energy is evenly spread wide out (the abrupt initial contrast loss

ending at about 1/40 frequency indicates the radius of this spread

as 40 times the cutoff frequency, or 40λF - over 30 times the Airy

disc radius). Odd but expected TE property - due to the relatively

small affected area (the RMS for 0.80 Strehl is whooping 0.28 wave)

- is that increasing the aberration does almost no additional

damage.

ROUGHNESS: ~1/14 and ~1/7 wave RMS of roughness

producing asymmetric PSF pattern, thus having contrast transfer vary

with its orientation relative to MTF bars. Due to the random nature

of the aberration, the P-V wavefront error can vary significantly

for any given RMS/Strehl level. IHere, the P-V error ranges from

-0.169 (blue speck on the wavefront map) to 0.374, and -345 to

0.745, respectively. RMS error also may not be as reliably related

to the Strehl as with most other aberrations.

PINCHING: 0.37 and 0.74 wave P-V of wavefront

deformation caused by edge pinching at a three 120°

separated points has the typical

SEEING ERROR: Averaged PSF/MTF effect of ~1/14

and ~1/7 wave RMS of atmospheric turbulence. The P-V error can vary

substantially (here is 0.43 and 0.86 wave, respectively). Seeing

error fluctuates constantly around the average, as do the

corresponding image contrast and resolution. Larger seeing errors

(1/7 wave RMS is rather common with medium size apertures) reduces

contrast level to that similar to twice smaller aperture for

low-to-mid frequencies, with some high-frequency transfer (iincluding limiting

resolution) advantage remaining.

MTF contrast transfer generalized to the RMS

wavefront error alone, regardless of the type of aberration is, as

shown by Bob Shannon, given by a product of aberration-free MTF and the Aberration Transfer

Function [ATF=1-(ω/0.18)2(1-4(ν-0.5)2),

where ω is the RMS wavefront error in units of

wavelength, and v is the

normalized spatial frequency; not to confuse with the

Amplitude Transfer Function - this

is the only place where the Aberration Transfer Function is mentioned] for any given level of the RMS error,

and aberration-free

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||