|

telescopeѲptics.net

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪▪▪▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪ CONTENTS

◄

6.6. Effects of aberrations: MTF

▐

6.7. Coherent transfer function, Fourier

transform

► 6.6.1. Aberration compounding and MTF, CCD contrast transfer, MTF limitationsPAGE HIGHLIGHTS Expressing combined effect of two or more aberrations through the MTF can be done, similarly as for the wavefront aberrations, either precisely, through a complex calculation, or as a single number extracted from statistically averaged probability (approximation). As the above graphs show, difference in the effect on performance of various aberrations with a similar RMS wavefront error level becomes more significant as the nominal error increases. For two or more aberrations combined, the effect is, on average, greater than either single aberration components alone. However, they do not add up arithmetically. For relatively small, unrelated or random wavefront errors, the combined effect is given by the square root of the individual errors squared, or

ωc=

(Σωi2)1/2

(58)

with

ωi

being the individual RMS wavefront error. Similarly, the combined effect

on peak intensity of the PSF (Strehl) and, thus, average MTF contrast

loss can be, for mostly unrelated smaller aberrations, closely

approximated as the product of individual Strehl ratios for any number

i of different aberrations, Strehl being, in fact, an MTF (contrast) degradation

factor:

The product

Sc

is a combined Strehl (the peak diffraction intensity ratio) for the errors

included; it also expresses the average MTF contrast level in units of the

average contrast level of a perfect aperture. This implies that for this

type of aberrations, the combined MTF as a product of the two aberrated

MTF - i.e. their contrast transfers at every spatial frequency.

The conventional minimum acceptable level of

optical quality - so called diffraction-limited standard - is 1/4 wave P-V wavefront error of spherical aberration

or, in more universal form, the associated 1/13.4 wave RMS (0.80 Strehl). That

corresponds to 0.42 wave P-V of coma, 0.37 wave P-V of astigmatism, and

so on. This criterion is not strict - it is a somewhat lose dividing line between good and bad

optics. In

fact, since it is, in the commercial environment, habitually applied to the quality level inherent to

optical surfaces alone, it is safe to assume that the actual

quality minimum is lower, perhaps significantly. In addition to

induced aberrations considered earlier, as well as chromatism, one of the factors lowering

optical quality in addition to that determined by the wavefront

aberration level alone is the effect of central obstruction.

Beside wavefront aberrations and pupil obstructions, contrast

degradation can be caused by detector properties. Specifically, contrast

transfer of a CCD chip depends on

its pixel size, relative to the system Airy disc diameter. Contrast

transfer in the final image is a product of contrast transfers of a

telescope and that of the CCD chip. According to Schroeder (Astronomical Optics,

p309), for square pixel with the side p in units of

λF, contrast transfer (MTF) is given by:

with ct

being the telescope MTF, the sinc term the MTF of CCD chip (the angle

pνπ is in radians,

converting to degrees in the numerator) and

ν the normalized spatial frequency

(for ν=0 cf

is undefined, but it approaches 1 as cf

approaches 0, thus represents

its limit value).

Sinc values for selected pixel sizes are

plotted to the left. For p=2, which for an ƒ/5 system and λ=0.5μ

corresponds to 5μ pixel size, contrast transfer drops to zero at ν=0.5

(from ct=sinπ/π=sin180°/π),

effectively halving the cutoff frequency of a telescope before

contrast

reversal (negative modulation values). In addition,

contrast level over all frequencies before reversal is degraded to the

level of a twice smaller perfect aperture, with the contrast after

reversal being a small fraction of the (original) contrast in a perfect

aperture (FIG. 102). Half as large pixel

preserves more of contrast transfer efficiency, but in order for it

to approach that of a telescope - assuming its optical quality is not

significantly below the usual standards - pixel size needs to be reduced to 0.5λF,

or 1/2 of the system's FWHM. According to the Nyquist criterion, this is

also the minimum needed for clearly resolved point sources at the

diffraction limit ~λ/F.

Since the first zero for the sinc factor falls

at pν=1, first zero of the

combined MTF is at the spatial frequency

ν=1/p, regardless of the MTF of

a telescope, as plots for p=3 and p=4 show. Hence, preserving the limiting MTF resolution of a

telescope requires p=1, or smaller. Some positive contrast

recovery at high frequencies does occur for p>2, but it is generally

insignificant vs. the overall contrast/resolution loss.

FIGURE 102: Additional contrast degradation in

42% obstructed system resulting from relative pixel size p, in units of system's

aberration-free FWHM (~λF).

The combined system+detector MTF is a product of the system's and

pixel's MTF (i.e. product of their respective

contrast transfers at each frequency). For p=2, contrast

drops to zero at spatial frequency

ν=0.5; it still retains

low negative, or reverse contrast (the bright lines become dark, and vice versa).

For an f/8 imaging system and no significant aberrations present, this

level of contrast loss would correspond to 8.8μ pixel size, for

λ=0.55m.

Smaller pixels deliver better contrast transfer, and are not prone to

the occurrences of the "negative" effect in the high-frequency range.

To nearly preserve contrast transfer of the system in this case, pixel

size shouldn't exceed 2.2μ. This requirement is significantly more

relaxed in

the average field conditions, mainly due to the actual FWHM at

the detector being larger up to several times (depending on the aperture

size and length of exposure) than the aberration-free FWHM's, as a result of blurring caused by

atmospheric turbulence.

At this pixel size, the sinc factor for

ν=0.5 (approximate MTF cutoff frequency

for extended bright low-contrast details for aberration-free aperture),

is sin45/(π/4)=0.9,

degrading telescope's contrast transfer at this frequency by only 10%.

Relative contrast degradation at this pixel size does increase for higher frequencies,

which will also slightly reduce the point-source cutoff frequency.

Obviously, aberration level substantially degrading the actual contrast

transfer of a telescope would correspondingly ease the limit to the

maximum pixel size needed to nearly maintain this contrast transfer

level. By significantly enlarging telescope's FWHM at the detector, the

ever present seeing error puts the actual pixel size limit significantly

above the formal Nyquist criterion level, for all but very small apertures. For

short- and long-exposure imaging, in order to determine the approximate limit to the pixel size

which nearly preserves contrast transfer efficiency of a telescope,

the λF unit in the Nyquist

criterion needs to be replaced with the respective

seeing FWHM.

The effect of aberrations on CCD imaging can be also assessed in the

context of ensquared energy.

Of course, other factors influencing CCD contrast transfer efficiency

also need to be considered, particularly with respect to

signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio, which

can significantly affect contrast transfer and overall detection

capability of imaging system. In general, the SNR ratio can be expressed

as

SNR=SQt/√SQt+N,

with S being the signal flux from the object, Q the

detector's quantum efficiency (defined as the ratio of detected vs.

incident photons), t the exposure time and N the sum of

all noise contributions, N=(BQ+D)t+R2,

where B is the background (sky) emission, D the detector's

dark count (thermally produced electrons within CCD chip itself) and

R the readout noise.

A few words about

limitations of the standardized MTF

in projecting its output to the actual observing. One comes from the

standardized MTF being strictly exact only for the object used:

parallel, contrasty, brightly illuminated dark and bright lines with

sinusoidal intensity distribution. For

different types of objects, both contrast transfer and cutoff frequency

(limiting resolution) may be different, possibly significantly. Also, the MTF assumes continuous

spread of energy; in other words, every line interacts with all the

energy reaching it from both, left and right. Actual observing objects

are finite, and the absence of continuous spread results in the outer

areas being subjected to less of energy overlapping than the MTF

assumes. It is particularly pronounced with small, or narrow objects (FIG.

103).

The consequence is better contrast transfer and

resolution than what the MTF (thus, also PSF and the Strehl) would

indicate, even for an object identical to the standardized MTF pattern.

Specifics of this effect vary with the object type, as well as the type and

level of aberrations present.

Finally, a limitation of the MTF - but not

OTF - is, as mentioned on the previous page, that it does not include

information on the phase shift and its possible effect on the image. Phase shift itself merely shifts

the MTF diffraction image laterally

with respect to the Gaussian (geometric) image, and shift of half the

phase (π

radians) will result in contrast reversal, i.e. switch of light

areas into dark, and vice versa. While neither is affecting the

definition of MTF pattern, which is evaluated at each isolated frequency

alone, an actual image will often contain multiple frequencies, either

isolated or in continuums. In such case, intensity distribution shifts

caused by phase shift can result in deformation of image vs. object,

which could also impair detail detection or resolution. Some examples of

this effect are given below. One of the objects used is the continuum of

frequencies contained in the MTF (aberration-free) resolving range, and

the other a radial test pattern (simulations generated by Aberrator;

aberrated images were made more contrasty than the original output, to

make the effects on patterns more obvious).

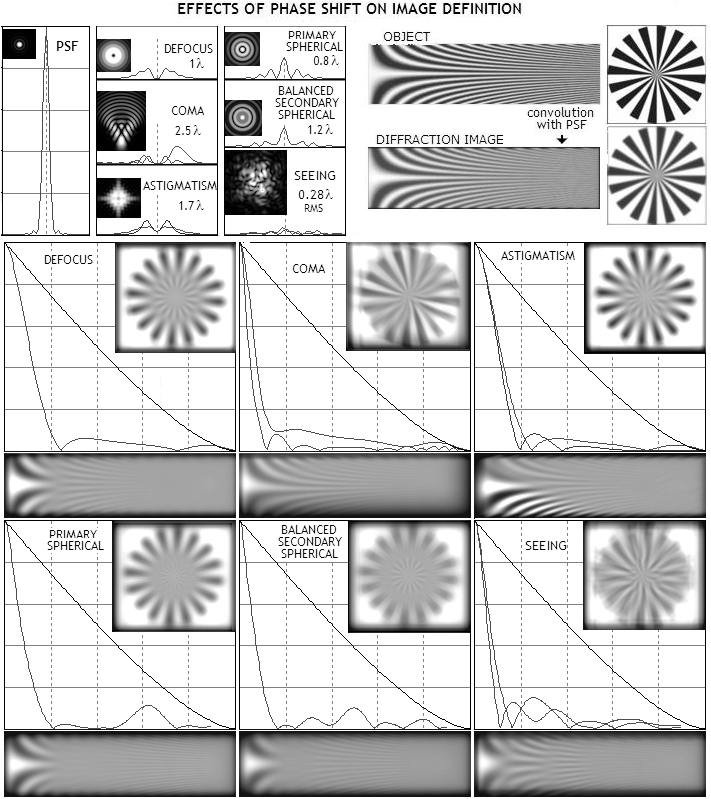

Aberration-free and aberrated PSFs are shown top left

(the plots are not proportional to the simulations scale-wise, but

either are among themselves, double PSF/MTF plots for asymmetrical

aberrations are for the best and worst PSF orientation). Magnitude of aberrations are chosen to

roughly produce the contrast transfer level corresponding to 1λ

wave P-V of defocus (with this large aberrations even the RMS error is

not a reliable indicator of error magnitude, and so is not the PSF

central intensity). Asymmetric aberrations, coma and astigmatism are

given at a rotation angle midway between their best and worst

orientation (indicated as two colored plots on their PSF and MTF graph)

- 45 and 22.5 degrees respectively (counterclockwise) - for which the

effect should be at least roughly averaged up.

Defocus causes contrast reversal, changing the

appearance of both images. Coma causes obvious asymmetry. Astigmatism

causes an interesting effect that appears as contrast reversal in the

star pattern, but only as intensity shift in the frequency continuum

pattern (the difference in appearance for the lower and upper left

portion of the image is caused by the diffraction pattern, rotated 22.5

counterclockwise, being nearly aligned with its "best" axis with the

former, and with its "worst" axis with the latter). Primary spherical

has lower contrast transfer in low and lower-mid frequencies,

compensated by higher transfer in the high-mid frequencies, but the only

change in image appearance is due to the insufficient contrast at some

frequencies. Balanced secondary spherical, even if generally similar to

the primary spherical, and at a roughly similar magnitude level, causes

noticeably different effects. And the effect of seeing is in some ways

similar to coma having, due to the extent of PSF energy spread, lower an

early contrast drop and, due to its asymmetry, detail deformations.

However, unlike coma it causes quite pronounced contrast reversals.

None of these effects that can significantly lower

image quality and detection level is indicated by the MTF. exception

being, of course, low contrast level in the case of spherical aberration

(spherical aberration also causes contrast reversal at the roughly

doubled error magnitude). While this may not be significant in general

terms, since this error magnitude is significantly larger than the

average found near axis in amateur telescopes, farther off axis this

level can be easily met and exceeded, thus effects of this type are the

reality. Also, larger amateur telescopes routinely operate at these and

larger error levels due to seeing, hence these kind of effects are no

stranger there, even on axis.

◄

6.6. Effects of aberrations: MTF

▐

6.7. Coherent transfer function, Fourier

transform

► |