|

telescopeѲptics.net

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪▪▪▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪ CONTENTS

◄

12. TELESCOPE EYEPIECE

▐

12.3. Eyepiece aberrations II

► 12.2. Eyepiece aberrations I : spherical, coma, astigmatism, field curvatureWhile the primary goal of the telescope objective is to transform flat incoming wavefronts into spherical, the eyepiece needs to accomplish exactly the opposite. If the wavefront entering the eye is not flat, the point-image on the retina will suffer from wider diffraction energy spread, just as it does when the wavefront formed by the objective deviates from spherical. The extent to which it will affect perceived image quality depends on the detail size and properties, as well as image magnification. If the front eyepiece focal plane doesn't coincide with the image plane of the objective, the wavefronts originating from object-image points will not exit the eyepiece flat, but curved (nearly spherical) and, as such, will be rejected by the eye in favor of the flat wavefronts coming from a point coinciding with the front focal plane of the eyepiece. The resulting error is defocus, easily correctable by moving the eyepiece to the proper position. If the object-image and the front focal plane coincide, and wavefronts entering the eyepiece are spherical, it will emerge from it flat if ocular is aberration-free. In the real world, these exiting wavefronts will be aberrated to some extent, and the aberrations are spherical, coma, astigmatism and field curvature, chromatism, image distortion and spherical aberration of the exit pupil. Due to a number of lens elements, aberration expressions for eyepieces are lengthier than for the objective. Also, eyepiece specs are commonly not known. For those reasons, eyepiece aberrations will be considered only in general terms. Before addressing specific aberrations, here's illustration of the main parameters of eyepiece aberrations using a simple Ramsden-type configuration.

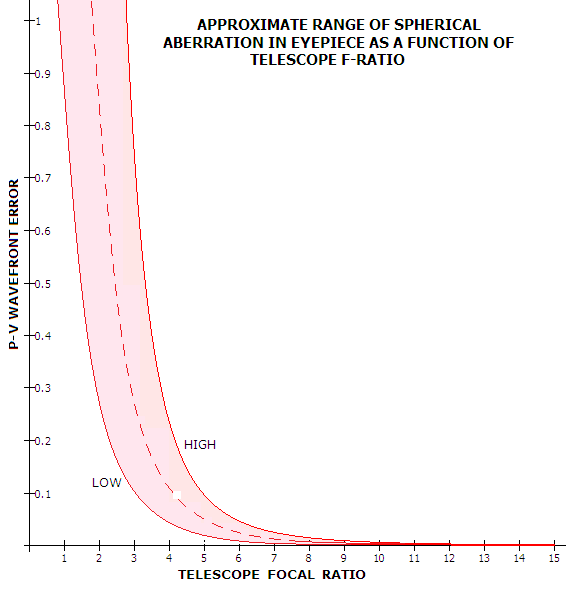

While even a single lens eyepiece can produce a good axial correction - due to the generally small cone footprint on eyepiece surface - its field correction is very poor, with the off-axis aberrations increasing exponentially due to the larger footprint combined with stronger radii. For instance, the eyepiece shown is a 10mm f.l. Ramsden with a pair of BK7 PCX lenses w/8.5mm radius of curvature, 6mm lens separation and 5.7mm from field lens to objective's image, as well as from eye lens to exit pupil. At f/10, it is aplanatic, flat field with low astigmatism (0.11 wave RMS 15° off axis). If the eye lens is taken out, both, footprint and refraction (requiring r.o.c. reduction to 5.2mm) at the field lens - which already contributes nearly all off the astigmatism - have to increase, resulting in several times larger astigmatism severely limiting usable field. In addition, multiple elements may allow for partial offsetting of aberrations between them, further reducing their final level. For that reason, eyepieces utilize two or more lenses. In the above example, the field lens "sees" the image formed by the objective as its object. Its aperture stop, however, is at the objective, because it is where the chief incident off axis ray intersects the axis. The eye lens "sees" the virtual image, formed by reverse extension of rays refracted by the field lens, as its object, and its aperture stop is at the point of intersection of the extended chief raj converging from the field lens and the axis. Thus, to both apply the lens aberration relations for displaced aperture stop. Obviously, in order for the eye lens to produce a collimated pencil, its object - the image formed by the field lens - has to be at the distance equaling its focal length. In this particular example, specific aberrations are very low spherical aberration, less than 1/100 wave P-V, most of it at the second lens due to the wider footprint (cone aperture) on it. Coma is practically zero on both lenses, due to the specific combination of object distance and stop separation for each lens. If, for instance, the focal length of lens changes, it changes the object and aperture stop locations relative to the lens' focus point, and the aberration is reintroduced, rather quickly. Nearly all of the astigmatism is on the field lens, and it is of opposite sign to that on the eye lens. The astigmatism is of the opposite sign to the Petzval curvature, offsetting it to produce flat, mildly astigmatic image surface. Visual detection of aberrations in the eyepiece doesn't depend on their magnitude, but on their apparent angular size. This applies to the aberrations that are enlarging central diffraction maxima, like coma and astigmatism; spherical aberration actually makes the central maxima smaller as it increases in magnitude, manifasting only as a loss of sharpness and resolution. The effect of off ais aberration will become just visible to the average eye as it reaches about 3 arc minutes in size. That is when point-like source start appearing as extended, although their shape is being clearly recognized at about 5 arc minutes apparent size (these numbers vary individually, possibly significantly). Knowing that the Airy disc diameter in eyepiece is given by 4.6F/f arc minutes (for 550nm wavelength), F being the telescope focal ratio and f the eyepiece focal length, the corresponding eyepiece focal lengths for recognizing the Airy disc are 1.5F and 1F mm, respectively. Since we don't see the Airy disc, but the central maxima which is always smaller, the actual focal lengths are also somewhat smaller. With the astigmatic blur close to field edge being up to several times the Airy disc diameter, or more, particulary in the conventional eyepieces with fast focal ratio systems, it can be detected even at the lowest magnifications. Eyepiece spherical aberrationThe wavefront error of spherical aberration in the eyepiece changes with the fourth power of the objective focal ratio. Thus, halving the objective F-number increases the wavefront error by a factor of 16. This makes eyepiece correction for spherical aberration critical. Even eyepieces superbly corrected at mid-to-small focal ratios, may become noticeably affected at large relative apertures. Since spherical aberration in eyepieces is also in proportion with the eyepiece focal length, longer f.l. units are more affected. However, they normally don't produce sufficient magnification to show the effect of aberration.

Modern-type eyepieces employing Smyth lens (negative field lens)

behave differently. In general, they tend to induce over-correction,

which also may become significant at very fast focal ratios, especially

when combined with the correction error of the objective that is of the

same sign. The Nagler-type eyepiece (Type 1) presented in the Rutten-Venrooij's

"Telescope Optics" raytraces to nearly 1 wave P-V of over-correction at

f/5. Since it is a 100mm f.l. unit, the error would drop to nearly 1/20

wave P-V with a 5mm f.l. unit at f/5. At f/4, it would be nearly

1/8 wave P-V. Should the objective be 1/6 wave P-V over-corrected at

f/4, the combined error would come to ~1/3.5 wave P-V of

over-correction.

As an illustration of eyepiece performance at very fast focal ratios, here's

raytrace of three actual designs: Nagler's patent from 1988(b), exceptionally

well corrected for spherical aberration even among the modern, complex designs (top),

Nagler's Plossl patent (bottom left), and a modern monocentric. The ray spot

plots are given for field center (left) and outer field point given below

focal length value (right).

Going from f/5 to f/3, this Nagler 2 does generate several times more

of spherical aberration, but since the error at f/5 is so small - the

Strehl indicates 0.003 wave RMS, or 1/100 wave P-V - it only gets to

0.022 wave RMS at f/3. The Plossl, which is near the top correction-wise

for the conventional eyepieces, already falls short at f/3. However, the

modern monocentric still holds it's ground with 0.9+ Strehl. Astigmatism

changes in inverse proportion to the square of f-ratio.

Eyepiece comaOff-axis aberrations are more pronounced in eyepieces, due to their large viewing angles. Coma is, in general, not significant in eyepieces due to it being usually minimized by design, and much lower than astigmatism, which cannot be reduced nearly as efficiently. The amount of coma wavefront error in a positive lens changes in inverse proportion to the square of the focal length, and in proportion to the third power of the cone width. In effect, for given field angle, it changes in proportion to the eyepiece focal length. It also changes in proportion to the third power of telescope focal ratio. Given eyepiece design, the 30mm f.l. unit will have three times the coma of the 10mm f.l. unit. Either will have eight times more of the coma wavefront error at f/5, than at f/10 telescope focal ratio.

As with the coma

originating

at the objective, eyepiece coma increases with the off-axis height in

the image plane.

However, it is

eyepiece astigmatism that usually dominates. It also depends on the lens focal

length and the cone width, being inversely proportional to the eyepiece f.l. and in proportion to the square of the cone width. In effect, for

given field angle it

is, as coma, proportional to the eyepiece f.l. but, unlike coma, it

changes in proportion to the square (not third power) of the telescope

focal ratio (note that the geometric blur size changes in proportion to

the focal ratio, but also with the square relative to the Airy disc). In other words, the wavefront error of astigmatism is four

times larger at f/5 than at f/10. Unlike coma, eyepiece astigmatism

increases with the square of apparent angle.

Also, unlike either spherical aberration or coma, lens astigmatism

- with the stop at the surface - is

independent of all three - refractive index, lens position factor and

shape factor; it only depends on the lens focal length. The means of controlling it with a set of positive lenses and lens

groups is generally limited, but the main reason why is it typically

strong in conventional eyepieces is that it is the third at the list of

priorities, after spherical aberration and coma. It is significantly

more complicated - or impossible, with simple designs - to have all three corrected.

0.01fe(ε/F)2<W<0.03

fe(ε/F)2,

in units of 550nm wavelength, where

fe

is the eyepiece f.l., ε the eyepiece apparent field angle in degrees

(radius),

and F, as before, the telescope focal ratio. Plots at left show

the range of astigmatism based on this approximation for three telescope

ratios, fast, medium and slow. It scales with the eyepiece focal length.

Taking 20-degree

near-edge AFOV for conventional eyepieces, it gives the following P-V

values of astigmatism for selected focal ratios and eyepiece focal

lengths:

The error scales with the square of AFOV, which means

it is four times smaller at 10° off axis, and 16

times smaller at 5°. The lower limit is not

strict; the error can be still lower, but not significantly. On the

other hand, poor designs can have significantly more astigmatism than

the upper limit, up to twofold, or so. It can be assumed, however, that

most of the conventional eyepieces made these days are closer to the

lower limit shown in the table.

For given magnification, eyepiece astigmatism scales

inversely to the focal ratio. For instance, if an �/4

with 10mm f.l. eyepiece has 2.5-7.5 waves P-V of astigmatism at 20

off-axis, an f/8 system with 20mm

eyepiece of identical design will have 1.25-3.8 waves.

An interesting example is Konig design given in "Telescope Optics" from

Rutten and Venrooij. It has practically cancelled primary

astigmatism (and well corrected higher-order term), at a price of somewhat

stronger than usual coma (FIG.

213). In terms of the RMS wavefront error, at 10° off-axis it is -

according to OSLO - superior to its low-coma, strong astigmatism variant

at both, f/10 and

f/5, with 0.033 and 0.23 vs. 0.065 and 0.33 wave,

respectively. At 20° field angle even more so: 0.16 and 0.7 vs. 0.94 and

3.7 wave. The enormous increase in the RMS error in the astigmatic Konig

variant reflects the devastating effect of combined lower- and

higher-order astigmatism. Yet, it is the type more likely to be found on

the market, because of the general notion that coma is less desirable

aberration form.

What actually puts the limit to usable field in a typical conventional

eyepiece is the combination of lower- and higher-order astigmatism. At

relatively small field angles, usually below ~15°, the higher-order

component is, in most properly designed eyepieces, negligible to

non-existent. But at once it creeps in at larger angles, it quickly

explodes with the 4th power of field angle, adding to the already

large lower-order component. This puts an end to the acceptable field

size.

As mentioned, eyepiece astigmatism

diminishes with the eyepiece focal length. A 10mm conventional eyepiece

unit has ~3 times lower astigmatism than 30mm unit, resulting in about

1.7 times larger linear diffraction limited field. However, the

difference is not that obvious in the eyepiece, due to shorter f.l.

eyepieces having proportionally larger magnification, which mainly

offsets the aberration decrease (FIG. 210).

For meaningful correction of eyepiece astigmatism it is necessary to

introduce a negative (Smyth) lens, which induces astigmatism of

opposite sign to that of the positive lens group. It also induces

Petzval field curvature of the opposite sign, resulting in both

astigmatism and field curvature minimized. Best known brand of this

kind, the Nagler, has astigmatism reduced up to several times vs.

comparable conventional eyepieces.

Field curvature in the telescope eyepiece is directly related to its

astigmatism. A hypothetical astigmatism-free eyepiece would form the

image coinciding with the Petzval surface. Being formed by a positive

power lens system, this surface is concave toward the eyepiece and,

considering relatively short focal lengths, rather strongly curved

(eyepiece's Petzval curvature, as well as other aberrations, are

determined by reverse ray trace, with collimated light entering through

the eyepiece's exit pupil).

Real world eyepieces, however, produce strong astigmatism,

particularly the conventional types. Usually, this astigmatism is of

opposite sign to the Petzval, thus abaxial points form astigmatic

surfaces less curved relative to the Petzval up to a certain level. At

the point when the sagittal astigmatic surface is half as curved as

Petzval curvature, best image surface is nearly flat (FIG. 211B).

Further increase in the astigmatism causes best image surface to become

increasingly curved to the opposite side (FIG. 211C).

It is possible that

astigmatism in the eyepiece is of the same sign as its Petzval (for

instance, due to unbalanced higher-order astigmatism) in which case the astigmatic image surfaces are closer to the eyepiece

than Petzval's, thus more strongly curved, and more so as

the astigmatism increases.

FIGURE 211: Astigmatism-free eyepiece will form flat field if the image formed by the objective is

also free from astigmatism and coincides with the eyepiece's

Petzval surface P

(A).

Astigmatism modifies the field curvature depending on its sign and

magnitude (B,C). If the sign is opposite to the Petzval's - usually the case -

sagittal astigmatic surface S forms on the convex side of

the Petzval's. Tangential surface T is always 3 times farther away from

the Petzval than sagittal, with the best, or median surface M

midway between the two.

Note that the curves show primary astigmatism. Eyepieces with strongly

curved lenses also generate secondary, higher-order astigmatism. Since it has significantly different rate of

increase than the lower-order form (4th and 2nd power of the field

radius, respectively), once it reaches considerable level at larger

field angles, it also strongly alters the initial field curvature.

Depending on the design particulars, the effect with respect to field

curvature can be either positive

(field flattening) or negative; it can also be positive up to a certain

image radius, then negative, or vice versa.

Flat eyepiece field means that all off-axis pencils exiti the eye lens

collimated, enabling the eye to focus on all points across the field

simultaneously. When the eyepiece field is curved, off axis pencils are

progressively more diverging, or converging, going farther off axis,

hence they cannot be focused simultaneously with the central pencils on

the retina (i.e. image points appear to be closer, for diverging

pencils, or farther away, for converging ones). This can be either

lessened or worsened when combined with the curvature of the image

formed by the objective, as shown below.

For simplicity, only best image surface is shown, i.e. field curvature

is assumed to be either the Petzval with zero astigmatism, or best

(median) astigmatic surface, when astigmatism is present. This is

simplification in that it is not only the image curvatures, but also

their respective astigmatism that interact, and since astigmatism

directly influences field curvature it is a factor that shouldn't be

entirely neglected. However, with the astigmatism of the objective being

typically negligible in comparison, the astigmatism factor can be

neglected in this respect for a general consideration, and assume that

the interactions of field curvatures alone will give a good

approximation of the combined field curvature.

Likewise, if the objective's image field is flat, the visual field will

have the curvature of the eyepiece's field (2a-c). With some

objectives which generate field curvature convex toward them, like

Gregorian two-mirror telescope, the combined field curvature forms in

the same manner, only the net sum with the same eyepieces is different (3a-c).

Astigmatism and field curvature of the eyepiece combine with those of

the objective, to form astigmatism and field curvature of the final

visual image. Just as the hypothetical astigmatism-free eyepiece would

need objective's image to be astigmatism-free, with the two Petzval

surfaces coinciding, in order to produce flat, astigmatism-free combined

field, an astigmatic eyepiece would need objective whose astigmatic

image would coincide with its own to result in astigmatism-free combined

image. Eyepiece astigmatism is normally significantly stronger than that

of the objective, especially for longer f.l. conventional eyepieces.

Hence the astigmatism of the objective doesn't have much of effect on

the final image: it is mainly determined by the eyepiece.

Short focal length eyepieces have proportionally lower astigmatism (as the transverse aberration; lower to the square of it as wavefront error, due to the smaller Airy disc), and

it can be more noticeably affected by the astigmatism of the objective.

Astigmatic surface profile of most amateur telescopes (Newtonian,

refractor, Cassegrain) is roughly similar in form to that shown on

FIG. 211C, concave toward objective, with the tangential

surface closer to it. Newtonian form is identical to it, while in

refractors and Cassegrain-like systems - including SCT and Gregory MCT -

sagittal surface is also concave toward converging light, and so is the

system Petzval; in Maksutov-Cassegrain with separate secondary, system

astigmatism can be nearly corrected, with the field curvature nearly

coinciding with its Petzval.

If the eyepiece has, say, form of astigmatism shown in (B),

twice stronger than the

astigmatism of the objective (i.e. double the sagittal-to-tangential

surface separation) having the form shown in (C), the tangential surface of the combined image will

be flat, with the sagittal unchanged, for the combined astigmatism

half that in the eyepiece alone, and median image curvature of opposite

sign, but of the same magnitude as that of the objective (Petzval surface becomes a factor only in

astigmatism-free systems). If the eyepiece has the same amount of

astigmatism, but with tangential surface flat and sagittal twice as

strong as in the former example (which requires stronger eyepiece

Petzval curvature), tangential surface in the combined image will have

curvature equal to that in the objective, with the sagittal surface

being as curved as in the eyepiece; the combined astigmatism is 50%

greater than in the eyepiece, but with the combined median surface

curvature somewhat weaker.

Gregorian-like two-mirror systems have, like Newtonian, Petzval surface

curvature of the same sign as typical eyepiece's Petzval, but considerably

stronger, with both sagittal and tangential astigmatic surface usually

convex toward converging light. With both telescope types, this allows

for the possibility of correcting both astigmatism and Petzval surface

curvature in the final image with matching eyepiece (easier in the Gregorian, whose Petzval

curvature is significantly closer in magnitude to that of the eyepiece).

Note that strong field curvature in eyepieces, if mainly result of

astigmatism as shown on FIG. 211C, does not implicate significant

defocus error, even without the ability of the eye to accommodate.

Sagittal surface is usually relatively weak, and the wavefront error

along it is identical to that along the tangential surface, with the

wavefront error along best (median) surface smaller by a factor of

1/√1.5.

In other words, it is the error of astigmatism that dominates

(but if the eye is unable to accommodate to the best image curvature,

the point images will be elongated).

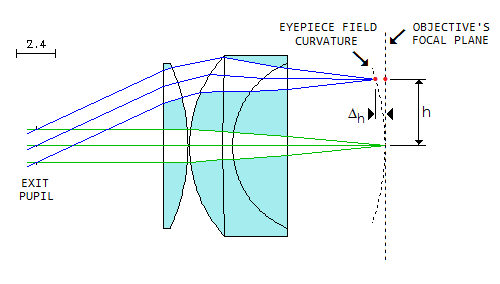

Needed eye accommodation to eyepiece field curvature (calculated based

on the thin lens Gaussian equation, thus only approximation)

depends on three factors, linear defocus of the off axis point in the

visual focal plane(∆), eyepiece f.l. (f) end eye f.l. (E) as:

A=(∆E A=∆ED/[f

for that defocus i.e. needed accommodation in diopters,

where D is the eye focal length in diopters (D~59; while the

optical f.l. of the eye, due to the image medium (n~1.33) is about 17mm,

giving D=1000/17~59, its physical f.l. is about 23mm). Most often,

point defocus ∆ is sufficiently small vs. eyepiece focal length,

and the relation simplifies to A~1000∆/f2. Taking A=1,

for defocus corresponding to one diopter, gives ∆~f2/1000.

Or, put simply, light from a point displaced

from the point-image defined surface in its image space

(which is in the actual setup the objective's image space, and object space

for the eyepiece), will not form a parallel exit pencil, but either slightly

converging one - for a point farther away - or diverging, if closer than the

distance producing collimated exit pencil.

Despite being numerically identical, only positive for extending, and

negative for shortening the focus, the two forms of accommodation are

very different to the eye. Shortening the focus, which requires

compressing the eye lens to a stronger radii than in its infinity

mode, is natural to the eye, and much easier than streching eye lens

out to weaken the radii, which it can do in a much more limited way.

Thus, assuming flat objective's image field, eyepiece field curvature

convex toward the eye is much preferred to the opposite shape (note

that field curvature resulting from reversed raytracing has opposite

sign of its actual field curvature, which is the case with distortion

as well; in systems w/o reversing reflection, light travels from left

to right, so the proper eyepiece orientation is with exit pupil on the

right side; in a Cassegrain-like system, eyepiece will have the

orientation shown, but the objective's field curvature will be

reversed due to reflection).

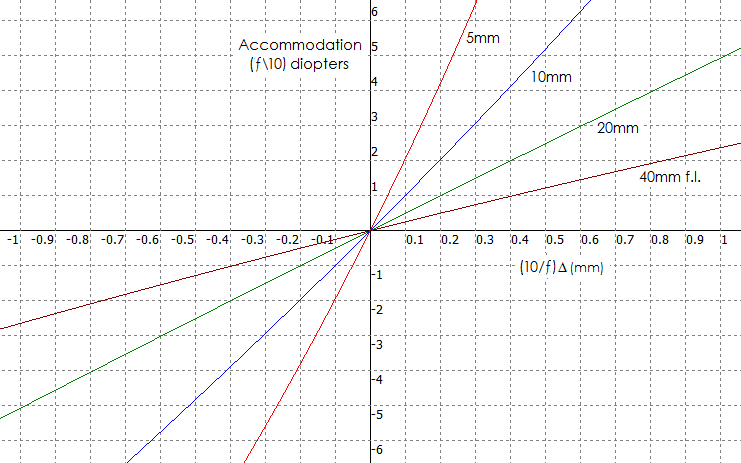

Above formulae imply that scaling eyepiece up results in lower

accommodation required, in inverse proportion to the focal length

(not in inverse proportion to the square of it, as it appears,

because the value of Δ also changes, in proportion

to the focal length). Graph below allows to extract the values

for point displacement and accommodation requirement for

eyepieces of different focal lengths. On the horizontal scale

it shows relative point displacement values, accounting for the

change in Δ with eyepiece focal length f, and on

the vertical scale the relative value of corresponding required

accommodation, given as the actual accommodation in diopters multiplied

with f/10 factor (these are a consequence of using Δ

that changes with eyepiece focal length in the above equation

for accommodation).

For instance, the actual point displacement for 0.1mm point

displacement in the 10mm f.l. unit, given by (10/f)Δ,

f being the eyepiece focal length, will be a bit less than

0.05mm in the 5mm unit, and 0.2mm in the 20mm unit. The

corresponding accommodation requirements will be 2 and 0.5 diopters,

respectively (from the value on the vertical scale divided with f/10).

Value of Δ alone represents point displacement

corresponding to 1 diopter accommodation; it is obtained by dividing the

scale value - in this case 1 - with 10/f. For the 5mm unit, it is

slightly less than 0.025. In other words, value of Δ corresponds to the scale value

only for the 10mm unit, as well as the scale value for accommodation requirement.

For different focal lengths, both change as indicated. The plots are

not straight lines due to the form of the equation, with those for

f<17mm being concave, and for f>17mm convex in the point of origin, 0;0

(the larger differential vs. 17mm f.l. the more so).

It is obvious that the same amount of accommodation will be required

if the situation is reversed, i.e. with a flat-field eyepiece, and

objective having the same amount of image curvature. However, since

the radius of curvature is constant, and field sagitta (s) for the

latter is given by s=h |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Degree of eyepiece correction for spherical aberration also varies with

the eyepiece type and brand. Best corrected conventional 5mm f.l.

eyepieces will have ~ 1/10 wave P-V of spherical aberration (under-correction) at

f/4, while those on the opposite end are closer to 1/4 wave P-V. This

doesn't necessarily mean that the telescope performance will be

noticeably affected. Most any objective contributes certain amount of

spherical aberration of its own. If it is of the opposite sign to that

of the eyepiece, the final result may still be admirable. But if the

error is of the same sign for both, it will result in inferior

performance. For instance, if the objective is 1/5 wave under-corrected,

and the eyepiece 1/8 wave under-corrected, their cumulative error will

be 1/3 wave P-V of under-correction. That is another example of the

actual telescope aberration level being determined by the combined

effect of both, objective and eyepiece.

Degree of eyepiece correction for spherical aberration also varies with

the eyepiece type and brand. Best corrected conventional 5mm f.l.

eyepieces will have ~ 1/10 wave P-V of spherical aberration (under-correction) at

f/4, while those on the opposite end are closer to 1/4 wave P-V. This

doesn't necessarily mean that the telescope performance will be

noticeably affected. Most any objective contributes certain amount of

spherical aberration of its own. If it is of the opposite sign to that

of the eyepiece, the final result may still be admirable. But if the

error is of the same sign for both, it will result in inferior

performance. For instance, if the objective is 1/5 wave under-corrected,

and the eyepiece 1/8 wave under-corrected, their cumulative error will

be 1/3 wave P-V of under-correction. That is another example of the

actual telescope aberration level being determined by the combined

effect of both, objective and eyepiece.

For instance, a field edge point 0.1mm off that imaginary point-surface in a 10mm f.l.

eyepiece will be as much removed from the actual (objective's) image point in the

flat image plane of the objective, thus the actual point it reimages will not form a

parallel exit pencil, but slightly converging (actual field point farther away,

illustration at left), or diverging (actual field point closer). Since change in the focal

length f of xf approximately corresponds to bringing object from infinity to a distance

of f/x (for x~0.1 and smaller), 1% difference in point distance vs. f.l. of the eyepiece means

that the rays coming to the exit pupil won't be parallel, but either converging, as if coming

from a point 100f=1m away, or diverging, as if coming from an imaginary point at the same

distance but behind the objective (eyepiece). Since 1m vs. eye focal length numerically

represents the eye focal length in diopters (59D), the defocus vs. infinity will be

approximately 1/59 of the focal length, or 1 diopter. For the case shown, with the actual

point farther away from the point that would form a parallel exit pencil, exiting rays will

be converging, forming in the relaxed (infinity) eye focus point shorter than

infinity focus, hence requiring eye lens relaxation (streaching) beyond that needed for

infinity in order to bring it to the retina.

For instance, a field edge point 0.1mm off that imaginary point-surface in a 10mm f.l.

eyepiece will be as much removed from the actual (objective's) image point in the

flat image plane of the objective, thus the actual point it reimages will not form a

parallel exit pencil, but slightly converging (actual field point farther away,

illustration at left), or diverging (actual field point closer). Since change in the focal

length f of xf approximately corresponds to bringing object from infinity to a distance

of f/x (for x~0.1 and smaller), 1% difference in point distance vs. f.l. of the eyepiece means

that the rays coming to the exit pupil won't be parallel, but either converging, as if coming

from a point 100f=1m away, or diverging, as if coming from an imaginary point at the same

distance but behind the objective (eyepiece). Since 1m vs. eye focal length numerically

represents the eye focal length in diopters (59D), the defocus vs. infinity will be

approximately 1/59 of the focal length, or 1 diopter. For the case shown, with the actual

point farther away from the point that would form a parallel exit pencil, exiting rays will

be converging, forming in the relaxed (infinity) eye focus point shorter than

infinity focus, hence requiring eye lens relaxation (streaching) beyond that needed for

infinity in order to bring it to the retina.