|

telescopeѲptics.net

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪▪▪▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪ CONTENTS ◄ 14.1. Early telescopes ▐ 14.3. Observatory telescopes ► 14.2. ATM TELESCOPES

•7" f/8 modified Sigler-Maksutov-Cassegrain

•30-inch f/5 Mersenne

Most ATM telescopes are of known designs, but their makers can customize

them to their liking. That makes them sort of unique, and adds to the

satisfaction of accomplishing, sometimes very challenging, creative

projects. With more complex systems, it all starts with a design created

and optimized through raytracing, as the basis for elements'

fabrication. And some of ATM telescopes are truly unique systems, out of

common knowledge of the amateurs and professionals-alike.

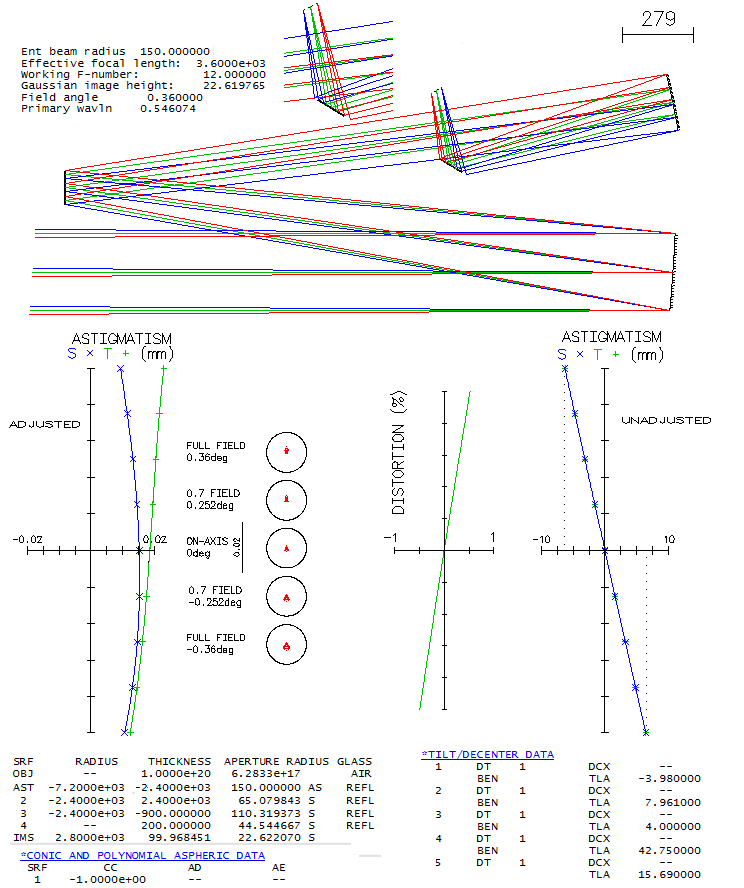

Marc Baril's 7" f/8 modified Sigler-Maksutov-CassegrainMaking Maksutov-Cassegrain of any kind is not for the faint of heart, primarily due to the full aperture Maksutov lens corrector, whose "easy" to make spherical surfaces have to remain within tight tolerances for the surface itself, the two surfaces relative to each other, and both relative to the meniscus thickness. A good example of it is Maksutov-Cassegrain made by Marc Baril, an amateur astronomer with professional background. Main modification to the Sigler's design was shortening the tube length which, according to Baril, did somewhat lower system's axial correction, but still allowed a high-level performance. Here is raytrace of the prescription given in the article.

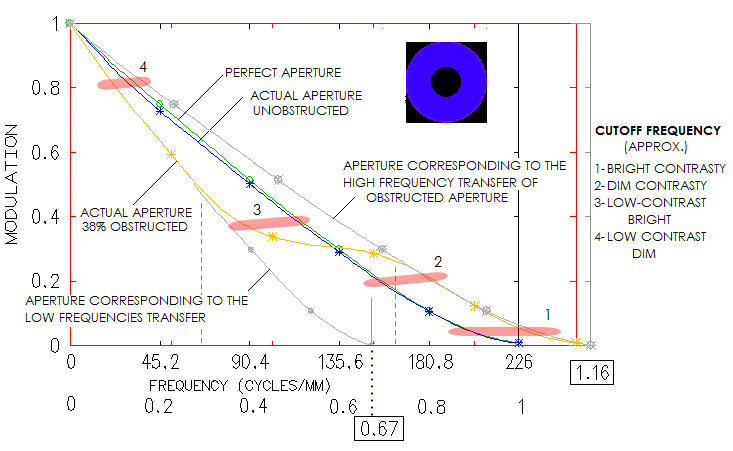

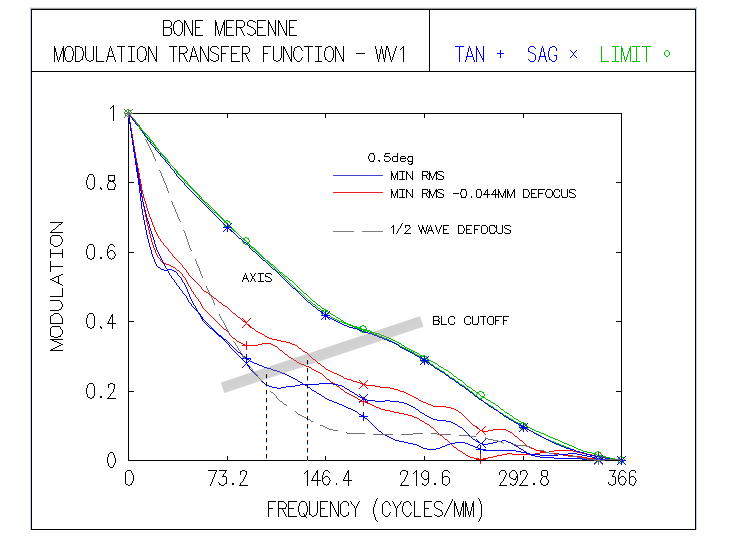

Design shows great field correction, with near-zero coma and astigmatism (it could, in fact, have 2-3 inches - or even more - smaller corrector separation without perceptibly affecting coma correction). Correction barely changes going from the field center to 0.5 degrees off axis. One thing to notice is that axial monochromatic correction of the starting design is a bit off (top left). It looks like undercorrection, but it is suboptimally balanced 6th/4th order spherical, with the lower order (undercorrection) being nearly twice larger than the (overcorrected) higher order. With the RMS wavefront error of 0.043, it is at the level of just a tad stronger than 1/7 wave P-V of lower order spherical. Baril mentions having a slight undercorection when arriving at the testing stage, which he removed by working the first corrector radius with a petal lap. While he thinks that what it did was slight aspherising, even just a slight strengthening of the first radius - going from 10.3507" to 10.344" - would do the trick. After taking care of undercorrection, we come to a design with 0.982 Strehl in the e-line, 0.927 in the F, and 0.926 in C. The polychromatic (430-670nm photopic) Strehl is 0.964. If we minimize the chromatism by bringing the colors tightly together strengthening corrector radii to 10.05" and 10.481", the two lines go to 0.972 and 0.976, respectively, with the e-line at 0.98. The polychromatic Strehl goes to 0.977. The Strehl figures are actually somewhat improved due to the 38% central obstruction, which took out the central deformation of the wavefront caused by spherical aberration. But the central obstruction did, of course, more damage than good at the level of system's PSF. Still, it's negative effect is commonly exaggerated. Baril states in his article that the biggest disadvantage of this design is its large central obstruction. How big a disadvantage it really is? The fact is that it reduces the wavefront error in all wavelengths - the larger wavefront error, the more so. If we would take it out, these same optical surfaces would produce wavefronts of lower quality. The central line, for instance, would go from 0.183 wave RMS and 0.982 Strehl, to 0.0225 wave RMS and 0.972 Strehl. At the same time, obstruction causes 0.86 drop in the relative central intensity of the diffraction pattern, with the second 0.86 reduction factor for the energy contained in central maxima - 0.73 reduction in total - coming from the reduced central maxima size. Due to the size reduction, central maxima is not only smaller, allowing higher limiting resolution, but also significantly brighter than what 0.73 degradation factor implies. In this case, central maxima is only 7% less bright than in a perfect aperture, in this respect corresponding to 0.93 degradation factor. So, while the nominal degradation factor is 0.74 (rounded from 0.73*0.982/0.972), it is also accompanied by 13% higher limiting resolution, and higher contrast transfer in the high frequency range. MTF compilation below illustrates the magnitude of both, loses and gains.

Here we see that the worst part of the central obstruction effect is lowering contrast transfer to the level of 33% smaller aperture in approximately 0-0.3 range of frequencies. In the 0.7-1 range the transfer increases to the level of 16% larger aperture, while over the 0.3-0.7 range we have transition from lower to higher transfer, extending all the way to the resolution limit of 16% larger aperture. Overall, nominal view favors obstructed aperture, which has contrast transfer advantage in nearly as much of the frequency range as the unobstructed, with extra high frequencies added beyond the resolution limit of unobstructed aperture. However, to better understand the implications, MTF frequencies should be associated with magnification. With the limiting resolution at cutoff frequency λ/D in radians (times 206,265 in arc seconds), magnification at which a general detail is magnified to 5 arc minutes (likely more near threshold of detection), needed for the average eye to recognize its shape is 300D/206,265λ, or 2.64D for the aperture diameter D in mm and λ=0.00055mm (67D for D in inches). For details of Airy disc size, 2.44λ/D, corresponding to 0.41 frequency, it is 1.1D, and half as much for twice larger detail (0.2 frequency). So we could say that high magnifications start, quite approximately, at 0.3 frequency. If so, the bad part of central obstruction effect falls to the range of mid and low magnifications, while the good part covers most of the high magnification range. That said, should be noted that the largest contrast drop for this obstruction, some 25%, is at about 0.4 frequency - somewhat deeper into the high magnification range - while diminishes toward the mid-to-low magnification range (<0.3 frequencies), down to 12% at 0.2, and 5% at 0.1 frequency. There are direct implications of different contrast levels on the limiting resolution. Taking approximate minimum contrast requirements for different object types from Rutten/Venrooij, we get that the obstructed aperture will have appreciably higher resolution limit not only for the conventional MTF limit (two bright lines, nearly identical to that for two near equally bright stars), but also for bright contrasty objects, like the surface of Moon (1 and 2, respectively). On the other hand, unobstructed aperture has higher resolution limit for bright low-contrast objects (3) and dim low-contrast objects (4). Obviously, we can't compare apples and oranges, so whether the effect of central obstruction is good, bad, or insignificant, will depend on the specific use. In all, the effect of central obstruction is a mixed bag, and certainly is not only bad. For photography, considerations are somewhat different, but the effect is generally considered less of a factor than for visual use. Summing it up, while it is not possible to execute the actual optics to its theoretical optimum, it is not even necessary. No mortal soul can see the difference of one or two 1/100s in the Strehl ratio. From Baril's article, it is very likely that his commitment to making this telescope as close to its design marks as he could, did bring it to the level where the difference vs. theoretical optimum didn't matter.

Sure, performance level would have been even better with a system with

slower primary, such as the original Aries' Maksutov Cassegrain, without

significant difference in the tube length. But if one wants a faster

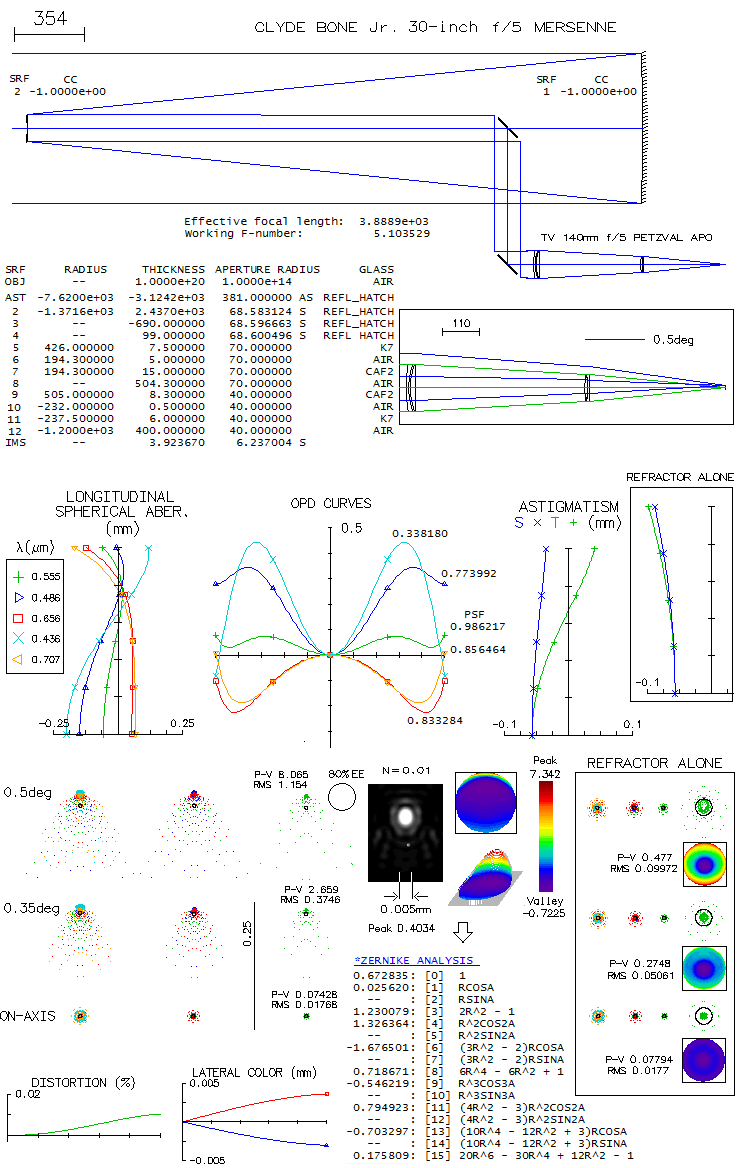

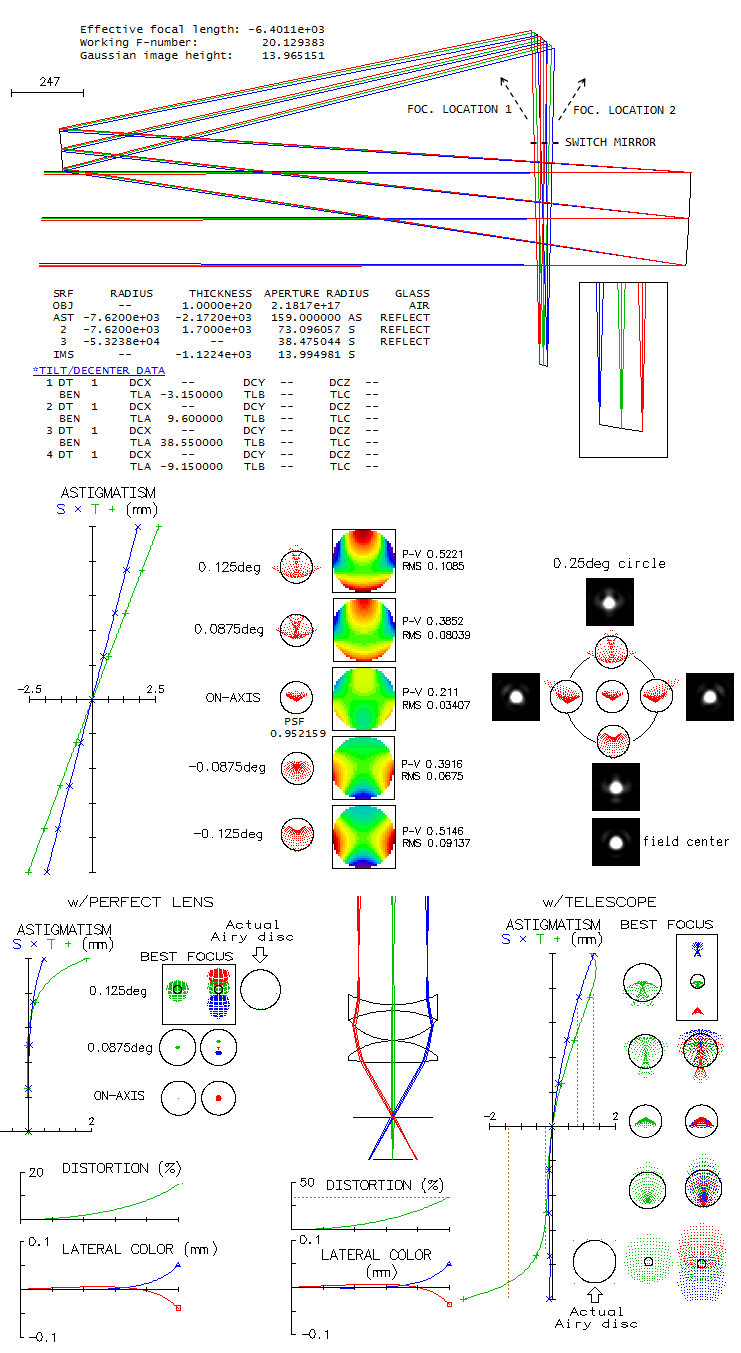

system, there is a price to pay. Clyde Bone Jr. 30-inch f/5 MersenneIn an S&T article from 1999 Clyde Bone (San Angelo, Texas) describes his 30-inch f/5 Mersenne-type telescope, for which he used Tele Vue's 140mm f/5 Petzval apo at the eye end (there is also an article on the Tele Vue site). The telescope was built with the highest standards, using, for instance, astro-Sital mirrors with 96% reflectivity - 1/16 wave primary, 1/10 wave secondary - and Pyrex flats with dielectric coatings (98.5% reflectivity). The two mirrors are confocal paraboloids, producing collimated beams free of aberrations (except Petzval image curvature, which is here -836mm). An image-forming system is required and, if the completed system is to be a visual telescope, it has to consist of an objective and eyepiece - i.e. telescope. Image below shows raytrace of such a system. Since no information on the Tele Vue refractor was published, a Petzval system that should be similar to it in its optical output is used to illustrate the combined performance level. It is a borderline "true apo" based on the errors in the four unoptimized wavelengths (F and C balance out at about 0.80 Strehl, and only the violet g-line is little over the required 1/2 wave P-V), but not according to its 0.917 polychromatic Strehl (photopic). This is mainly caused by keeping the violet g-line error nearly as low as possible, causing the blue and red - particularly the former - to be suboptimally corrected. If the F-line error is minimized, its Strehl increases to 0.856 (w/0.898 C-line), g-line drops to 0.183, but the poly-Strehl is up to 0.945 (all needed to accomplish this is to change R5 i.e. 9 in this prescriptionto 520mm, and R8 i.e. 11 to -237.7mm; that produces f/5.15 system, rescaling it to f/5 would lower the poly-Strehl to 0.934). The actual secondary is six inch in diameter, but in order to avoid stopping down the aperture, the reflected beam width has to be no more than 140mm (here, it is slightly less, which produces an effective f/5.1 system). Note that refractor alone is evaluated at f/5, and the setup used only stop at a distance of the Mersenne system exit pupil (located at -k+k2 from the secondary, toward primary's focus, in units of primary's focal length, with k being the marginal ray height of the axial pencil at the secondary, in units of aperture radius). Prescription with the complete system given with the image is a compilation of two prescriptions (OSLO Edu has 10-surface limit). This means that the nearly flat field here in the actual telescope corresponds (approximately) to the Petzval image surface, somewhat lessened by astigmatism induced by lens objective processing diverging pencils from the secondary (shown on astigmatism plots). Also, the 0.5° field radius in a 700mm f.l. refractor corresponds to 0.09° in the 3889mm f.l. system (will be explained ahead).

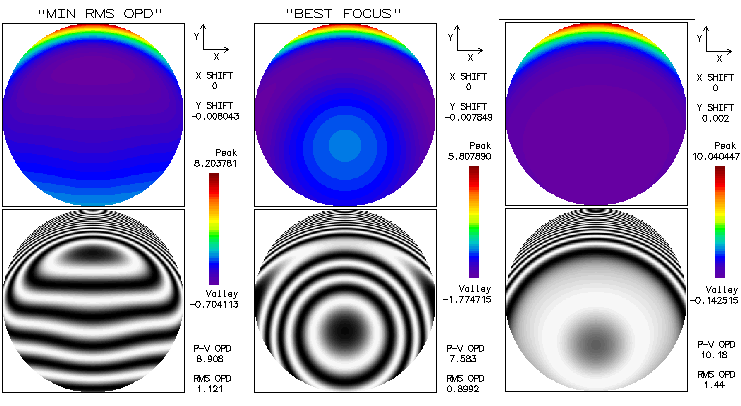

The field is limited to 0.5° i.e. 0.09° radius, since off-axis aberrations are already significant. It is a consequence of the widely separated aperture stop (also, as the box right from prescription shows, vignetting at the objective lens becomes significant). Part of it is that the incident ray angle is magnified after reflection from the secondary. With infinite secondary magnification, incident angle is magnified by a factor 1/k; with k=0.18 here, the incident angle magnification is 5.56, i.e. 1° angle at the primary becomes 5.56° at the lens objective. Hence, 0.5° at the lens objective is 0.09° in the actual system (linear field height is identical in both, since the two respective focal lengths differ by the same ratio). The central obstruction is 20% linearly, or little more. Since its effect on off-axis aberrations here is negligible, it is omitted to keep interferogram patterns intact. Also, to show the original polychromatic Strehl of the refractor, which would be superficially increased in the presence of obstruction (specifically, it would increase the poly-Strehl to 0.934 - and to over 0.95 with the F-line error minimized - as a result of small wavefront error decreases in all wavelengths - the larger error, the more - hence only in part reflecting better chromatic correction; on the other hand, that small gain is paid for with a 0.96 drop in central intensity - to the actual 0.897 - plus another 0.96 ratio energy loss due to the smaller central maxima, for the final 0.87 central maxima energy ratio on axis). Wavefont map for the 0.5° point shows that most of the P-V error comes from raised edge on one side. Because of that, both P-V and RMS error are somewhat misleading, implying larger than the actual error. The main wavefront component is in the blue area, less than 1/3 of the entire 8 wave P-V error. Zernike analysis gives as dominant terms primary coma (#6), astigmatism (#4) and defocus (#3), followed by secondary astigmatism (#11), coma (#13), primary spherical aberration (#8) and trefoil (#9). However, the primary spherical aberration term indicates 0.32 wave RMS, much more than what is present on axis; this means that most of this term is actually lateral spherical aberration, a secondary Schwartzschild aberration of the same form as primary spherical, but increasing with the square of field height. Also, raytrace shows that coma-like ray spot plot grows significantly faster than in proportion to field radius, indicating presence of other "odd" secondary aberrations, such as lateral coma (secondary Schwatzschild aberration, of the same form as primary coma, but increasing with the cube of field radius), and probably some others. Diffraction simulation for the 0.5° point (e-line) shows some elongation, but still well formed central maxima, embeded in a tight, bright ring (mostly due to 0.01 normalization); however, 80% energy radius is 0.0286mm (large black circle), much larger than the Airy disc (not sure how adequate is this number, since it could be based on PSF centroid location, which is here by some four Airy disc diameters - or 0.025mm - from the PSF peak, indicated by the dense ray area above the Airy disc circle on the ray spot plot). The bright central oval is similar in area to the Airy disc, but the peak intensity is only 0.40, indicating energy comparable to that with 1/2 wave P-V of spherical aberration (note that the peak intensity is much higher than central intensity, due to intensity shift from the PSF center). Box bottom right shows corresponding ray spot plots for the refractor alone, for the same 0.5° radius field; evidently, all off axis aberrations are a consequence of the large stop separation. There is a discrepancy between the 0.5° wavefront error magnitude and the corresponding PSF. Even if limited to the blue area on the wavefront map, it is as much as 2-3 waves P-V, not agreeing with still quite compact central maxima. Taking a closer look, we see that OSLO default wavefront map is for "minimum RMS OPD" (image below, left).

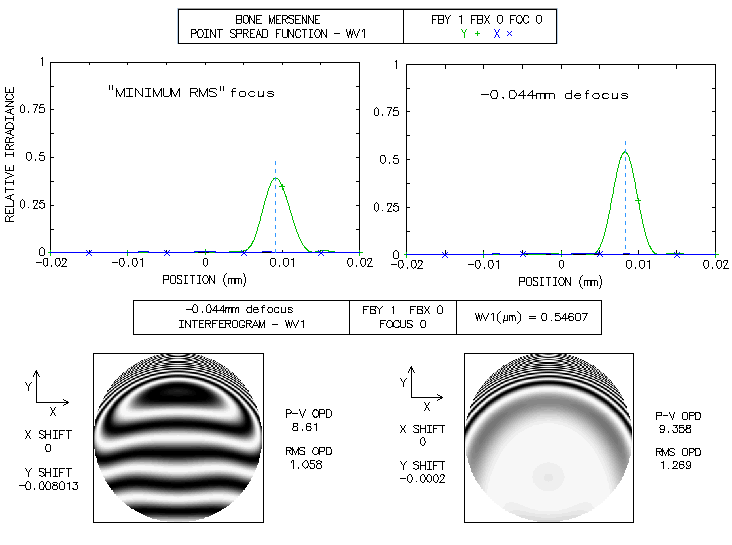

The corresponding interferogram shows that most of the blue area is tilted, with a small depression going into the raised upper edge. With the fringe-to-fringe separation being 1/2 wave OPD (optical path difference), the tilt of the blue area is little over two waves. Since tilt itself doesn't degrade point image, merely moves it in the direction of tilt, all needed to find the wavefront corresponding to the best image is to center it on that point (the raised edge adds another 5-6 waves, but it cannot be optimized tilt-wise simultaneously with the remaining, larger portion of the wavefront; its energy is, therefore, widely spread, contributing very little to the central diffraction maxima). The second OSLO option, "best focus" displays wavefront that combines tilt with a significant defocus over the blue area (middle). It actually has lower both, P-V and RMS error, with only a slight difference in the vertical shift (Y; the defocus shift along Z axis is not shown). In order to correct for the tilt alone, the third option, "reference ray intersection" needs to be used. Entering 0.002 Y-shift to the default coordinates, brings out the wavefront shape over the blue area for the best image proximity (right). It shows that most of this area is a low-aberration region, outlining a two-circle-intersection shape, oriented horizontally (the nominally higher overall P-V and RMS are the consequence of a larger error in the raised area, which is of little importance since it was already mostly wasted with respect to its energy contribution). This explains both, vertical elongation of the PSF central maxima and its integrity. Unfortunately, OSLO Edu has no option to calibrate PSF output with other than default data (it produces the best diffraction image decentered, in the process of generating PSF simulation for a wider area). However, entering -0.044mm defocus produces interferogram similar to that on the left, only with somewhat less of tilt in the blue area. For this point, PSF peaks at 0.52, suggesting it is the best focus (image below). Note that the actual PSF peaks are lower by 0.96 factor, or little more, due to the effect of central obstruction.

Note that even with OSLO making vertical shift adjustment, it is not the wavefront centered on the PSF peak, since it was looking for the "minimum RMS" error, and found it at an image point with still significant tilt error in the main, lower portion of the wavefront. If we manually enter -0.0002 shift - which should be equivalent of +0.0078 shift with respect to the default - we see interferogram nearly corrected for tilt and other aberrations (except a roughly 1/4 wave zone) in an area somewhat larger than with the "minimum RMS" focus corrected for tilt, which should be the reason for the higher PSF peak. But the P-V and RMS wavefront error are again larger for this point. This illustrates why both, nominal P-V and RMS wavefront error become less reliable indicators at large error levels. The "best focus" option is supposed to find what it promises, but it evidently doesn't always work as planned. Contrast transfer plots below show the defocused image at 0.5° as having appreciable higher contrast transfer than the "minimum RMS" focus. Note that these plots do include the effect of 20% linear central obstruction, omitted above.

The contrast advantage results in a significantly better limiting resolution of the defocused "minimum RMS" image for bright low-contrast (BLC) details. For comparison, dashed plot shows contrast transfer for 1/2 wave of defocus (unobstructed aperture). Tolerance to miscollimation between the mirror and telescope axis is comfortable: 5mm decenter will lower the central e-line Strehl to just below 0.95, while 0.5° tilt at the objective - implying 4.4mm axis-to-axis deviation 0.5m behind - lowers the Strehl to 0.96. However, 1° tilt already induces over 0.4 wave P-V of all-field (even magnitude across entire image) astigmatism, with the Strehl dropping to 0.73. Miscollimated secondary would induce combination of tilt and decenter. Considering large separation, it is the most sensitive part of the system. As little as 0.1° of tilt would translate to 5.5mm decenter combined with 0.2° tilt.

Replacing the above Petzval refractor with two others (FPL53/ZKN7 and

FPL53/BK7; the former has 0.999 central line Strehl, similar error magnitude in the g-line,

but tighter rest of them, resulting in 0.954 polychromatic Strehl,

while the latter has the central line Strehl already below 0.95,

due to more of higher order spherical residual), all with different

limits to spherical aberration correction

show that off axis aberrations in this setup mainly result from

uncorrected spherical aberration in the refractor: the more of it, the

larger off axis aberrations induced (uncorrected off axis aberrations also are a

factor when present). Since in this demonstration the refractor limit is at

0.018 wave RMS, or less than 1/16 wave of primary spherical, the actual units

would produce more of off axis aberrations, and significantly so. For instance,

the FPL53/ZKN7 combination has only 2.4 wave P-V wavefront error of

the same form at 0.5°, and we are talking 1/51 vs. 1/16 wave P-V

of primary spherical aberration (the FPL53/BK7 combination, with 1/8 wave

P-V of primary spherical equivalent, has as many as 22.3 waves P-V

at 0.5°). Considering

that this field size (0.18° diameter in the actual telescope) is

already within its medium-high magnification range, there is no room to absorb further field

definition worsening. It is wise not to push too far with the

objective speed: all else equal,

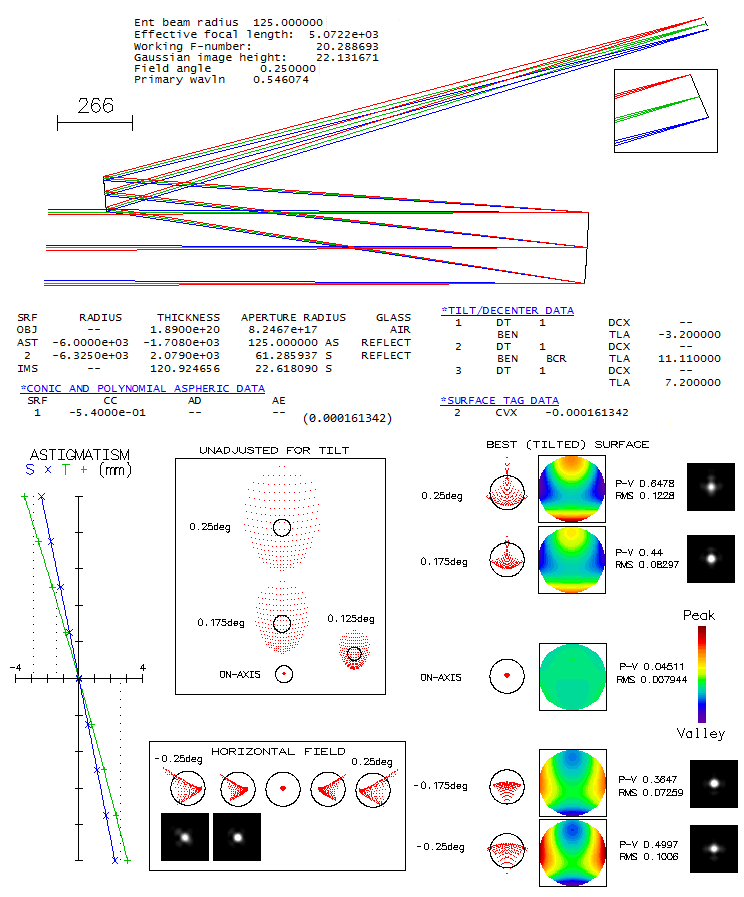

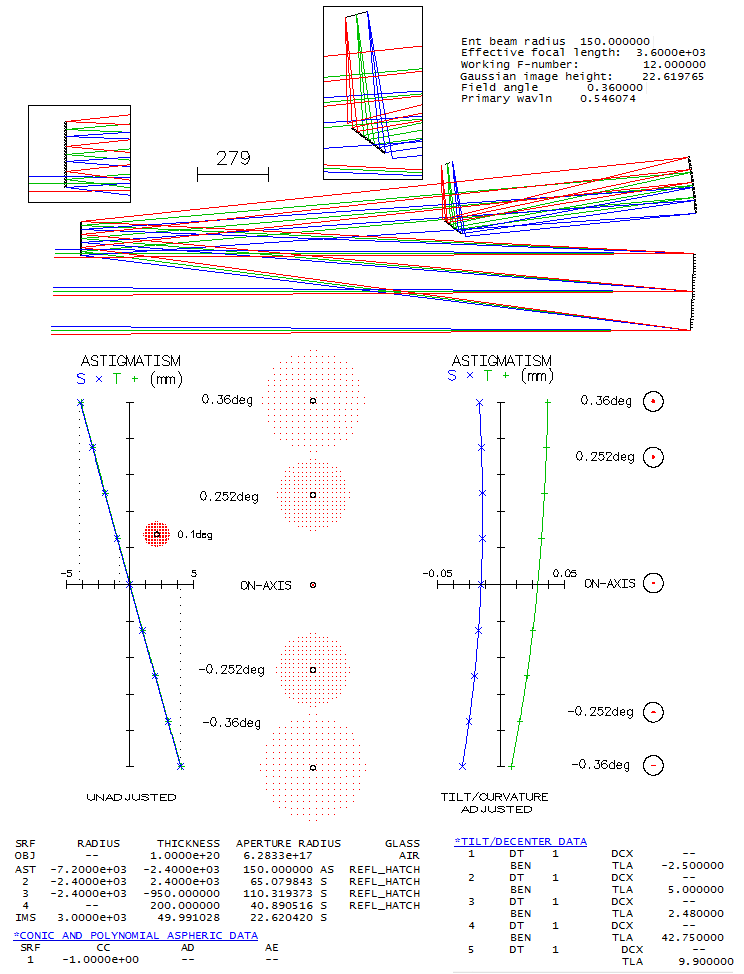

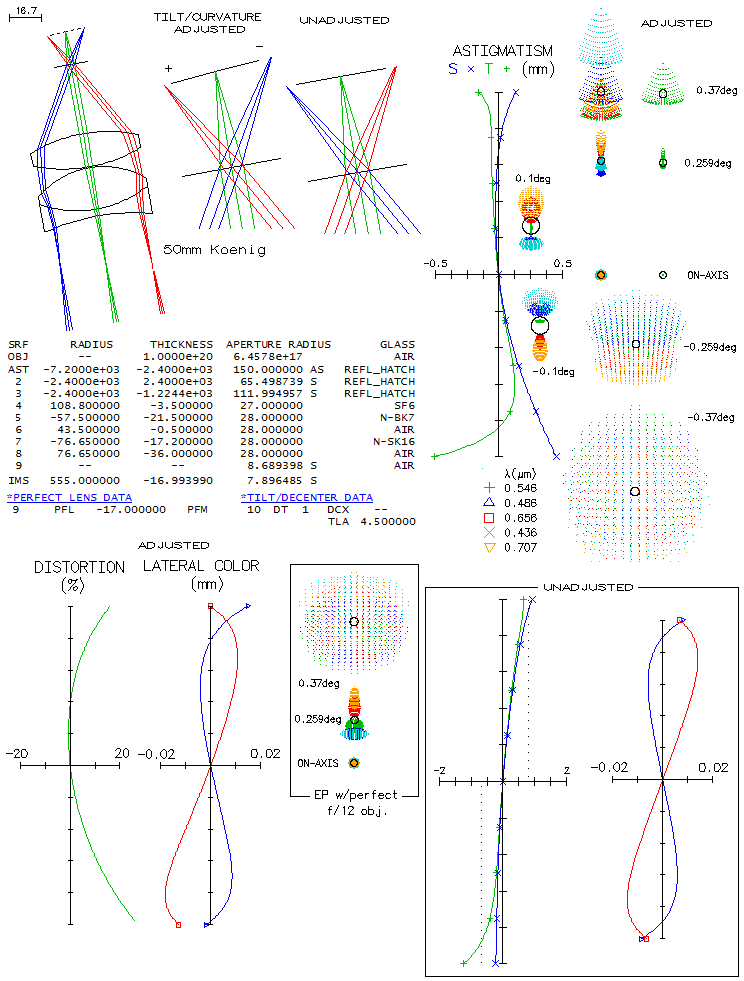

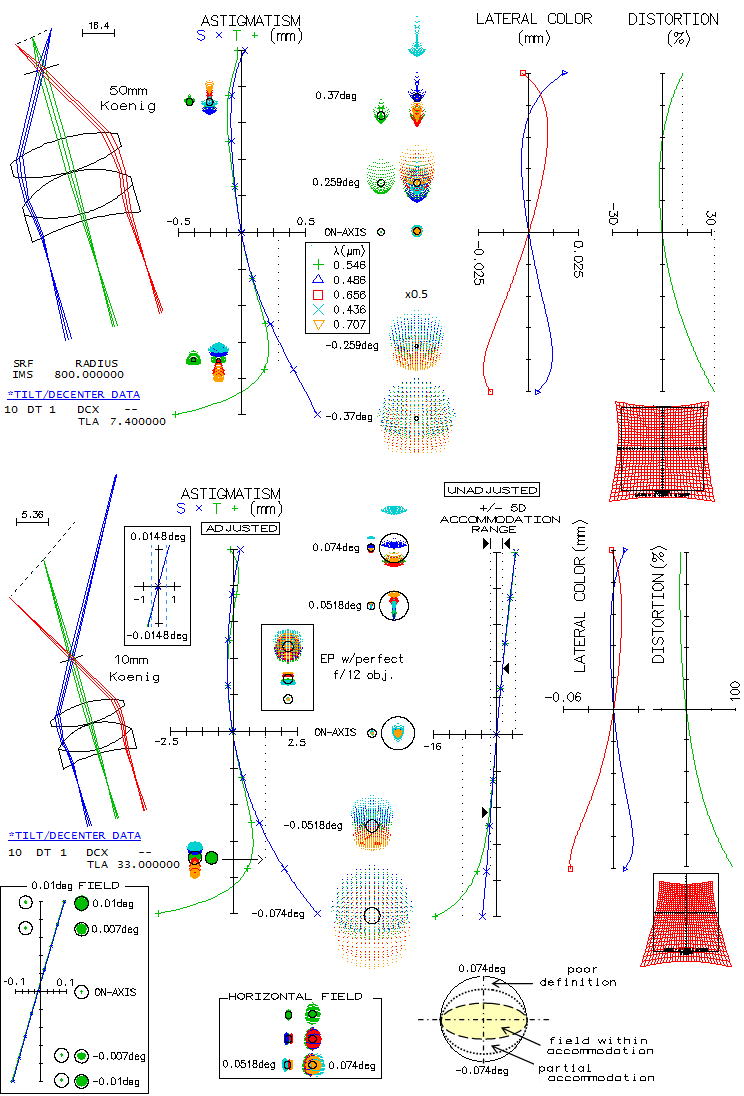

an f/6, or f/6.5 could do noticeably better in this respect than f/5. Terry Platt's 318mm f/21 Buchroeder "Quad-Schiefspiegler"Described in detail in Tonkin's "Amateur Telescope Making", this tilted-mirror system stems directly from Kutter's Schiefspiegler, with the third mirror added to cancel out astigmatism once the primary and secondary are arranged to cancel out coma (in the book it is called "quad-schiefspiegler" but since reflecting flat does not influence system output, it is a three-schiefspiegler). Reflecting flat is added in order to create two alternative focus locations, as indicated below. However, since it doesn't influence raytracing, and the telescope is fully operational without it, it was omitted from consideration. Primary mirror is aspherized (-0.55 conic) in order to minimize axial aberration, with spherical secondary and tertiary. Field angle is chosen to create image that fills out 1.25-inch barrel.

Astigmatism plot reveals significant image tilt. At the field edge, defocus due to the tilt is over 2mm, or over 1 wave P-V. However, what matters is how much of accommodation it will require in the image formed by the eyepiece. Axial correction is much better than in the Schiefspiegler (considering three times larger aperture), with the design limit better than 0.95 Strehl. According to Zernike wavefront decomposition, nearly 90% of the axial aberration is trefoil, with some residual coma. Longitudinal astigmatism of 0.85mm at the top edge (somewhat less at the bottom) implies 0.44 wave P-V wavefront error of astigmatism, which makes it dominant aberration in the outer field, with small contributions from trefoil and coma. Field aberration is not radially symmetrical, but it is relatively insignificant since at the very edge of the field central diffraction disc remains well defined. The maker of this telescope states that the image tilt - which is over 9° - does not significantly affect observing. It shouldn't be a surprise, considering the slow f-ratio, but it can be informative to assess it specifically with raytracing. Using 30mm f.l. 2+1 Koenig design, ray spot plots are shown for a perfect telescope (bottom left) and the actual telescope (bottom right). Note that the field angle is too large for this particular eyepiece design, requiring lenses larger than 1.25 inch barrel, and resulting in a sharp increase in the field edge aberrations (the corresponding undistorted field of view is over 53 degrees which, with 15% positive distortions produces 61° AFOV; a bit too much for a 50° AFOV design). Except the perifferal field, telescope aberrations dominate, which was to expect with this slow f-ratio. The effect of image tilt only shows toward field edge, increasing eyepiece aberrations on the bottom, and decreasing them on the top (the two field sides should have edge astigmatism at the level of the eyepiece in a perfect system). Accommodation required for the field edge is less than 1.5mm which, for 30mm f.l. eyepiece i.e. diopter equaling 0.9mm, translates to nearly 1.5 diopter of accommodation (infinity to 0.67m), positive on the field top, negative on the bottom. Without excessive edge astigmatism of the eyepiece, accommodation required would have been yet smaller.

In all raytrace confirms that the telescope, as a design, offers

well corrected field despite nominally significant image tilt.

That, however, assumes well collimated system. The 0.80 axial Strehl

tolerance for tilt is 0.025° (less than 1/14mm deviation

at the edge) for the primary, 0.05° for the

secondary, and 0.035° for the tertiary (for the aberration

induced by tilt added to the existing design minimum). Since this is

with the "tilt and bend" choice "on" - meaning that change in tilt

of the primary automatically adjusts axial position of the

secondary and tertiary (and change in the secondary's tilt adjusts

position of the tertiary) - the actual tilt tolerances should be

tighter. On the other hand, secondary and tertiary

are relatively insensitive to decenter (up to a few mm still leaves

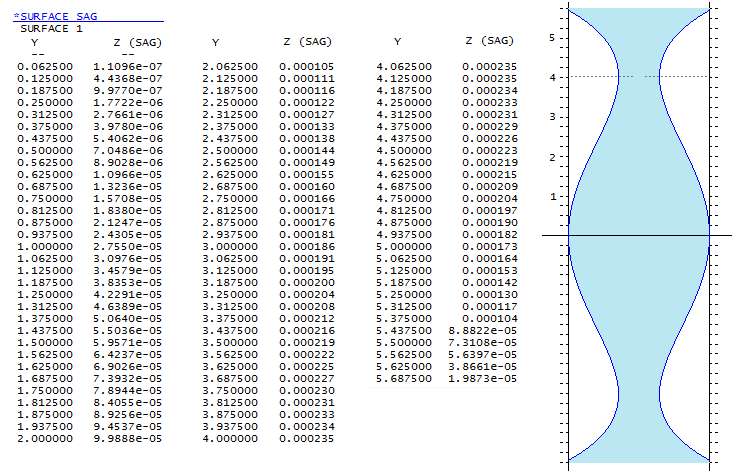

the Strehl well above 0.80). Bratislav Churchich's 146mm f/3.9 Wright cameraMuch less well known than its older cousin Schmidt camera, the Wright camera is not as well corrected, but has features that can make it preferred choice for some applications. In relatively slow systems, correction difference becomes less important, and its better compactness and inherently flat field can overcome the disadvantage of having to make an oblate ellipsoid for the primary and twice stronger Schmidt-type corrector. The latter apparently wasn't an obstacle for Churchich, who in order to make the camera more compact decided to go with even more strongly aspherized primary (nearly 1.5 conic), which also required as much stronger Schmidt corrector. As he describes in the same Tonkin's book, he stopped a bit short of the optimum primary conic (1.5) preferring to keep an exceptionally smooth figure. All this makes his Wright camera different from the standard. The corrector was made with 70.7% neutral zone, being the easiest shape to fabricate, but it also has the lowest spherochromatism (86.6% neutral zone has the smallest blur, but over 2.5 times larger wavefront error). Table below describes the perfect Schmidt profile needed for this instrument. Any deviation from it generates wavefront error by a 0.517 ratio (e-line), since the light speed in the BK7 glass vs. air is 1/1.517:1.

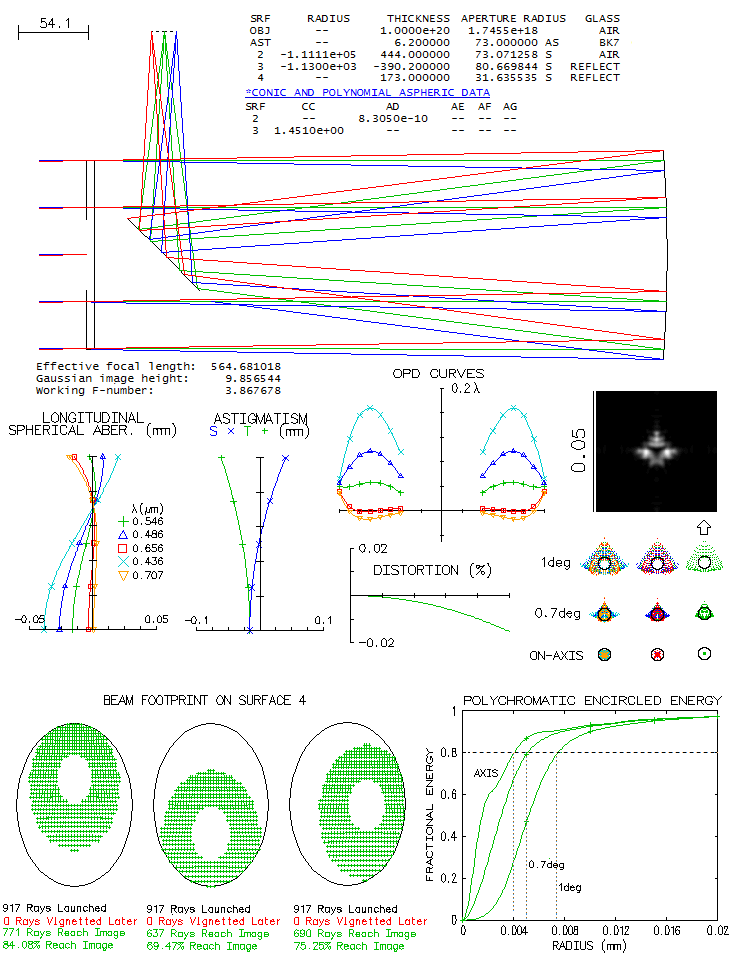

It shows that its maximum depth is less than 10 waves of 550nm light, i.e. that corrects mirror wavefront error 1.517 times smaller, around 6 waves P-V. The diagonal mirror is 55mm in diameter, taken as the size of central obstruction. Raytrace of this system below assumes perfect surfaces.

Due to the relatively slow focal ratio, chromatic correction is excellent, comfortably within the "true apo" requirements. The ray spot plots show residual coma (about 0.80 Strehl large at 1° off), but it is low enough not to significantly alter the shape of diffraction image (for fully canceling coma, either primary conic of 1.5, or corrector separation of 460mm are needed). The diagonal is not quite large enough to fully illuminate 2° field (it is raytraced w/o offset, but in the actual telescope is offsetted to be centered under the focuser). At the field edge, vignetting is about 10% (taken as that on the horizontal ends of the diagonal, the 3rd from left), which is within acceptable. Note that 711 out of 917 rays is what remains after central obscuration.

Since the main purpose of the instrument is imaging, what really

matters is size of the circle of energy. In this case, the camera

places 80% of energy into 8-micron circle on axis, 10-micron

circle at 0.7° and 14.8-micron circle at 1°. Angularly,

it corresponds to 2.9, 3.6 and 5.4 arc seconds. The actual star

image, as the diffraction images implies, is a bit larger, some

17 microns 1° off (of course, before seeing-caused bloating). The

Airy disc for an f/3.9 system is 5.2 microns in green light (546nm)

but these numbers are for the five wavelength from 436nm to 706nm

with even sensitivity. Since neither photo emulsion nor CCD have

flat sensitivity in that range, the actual circle sizes are somewhat

smaller. In this case, they were smaller than the typical photographic

blur, despite the unplanned, not negligible spherical aberration

residual. If the system was built as the standard Wright, with

a weaker primary and corrector, the 80% energy circle 1° off

axis would have been 13 microns, not much smaller than 14.8

microns in Churchich's customized camera (if optimized by

going for 1.5 primary conic,

the circle would measure 13.6 microns). Dan Cassaro's 11.4-inch f/4.3 Slevogt-Schmidt cameraAlthough still in making, this ATM camera posted at the CloudyNights forum is both, interesting and challenging. In order to obtain flat field with the Schmidt corrector and two spherical mirrors, corrector needs to be widely separated from the mirrors. The alternative is the Write-Schmidt, less than half as long, but with significantly more field astigmatism, and requiring a hard to make oblate ellipsoid as the main mirror. Its advantage is significantly smaller central obstruction, but if field quality is main concern, Slevogt-Schmidt is the way to go.

Design data posted at the forum describe a 11.4-inch f/4.33

Slevogt-Schmidt with f/2.294 spherical primary. It implies

secondary magnification of 1.89 which, for given back focus

distance, supplies necessary data to calculate the rest of

needed parameters: mirror separation, i.e. hight of the

marginal ray of the axial beam at the secondary, secondary

radius of curvature, corrector separation and aspheric

coefficients (mirror and corrector separations are already

given with the system, as well as secondary radius of curvature,

but the design usually starts with the primary, final f-ratio

and back focal length as the basis for calculating remaining

parameters). In general, in order to have flat field

Slevogt-Schmidt needs to have secondary radius of curvature

about 0.96 of the primary's, and secondary magnification about

1.8. Denoting needed parameters as

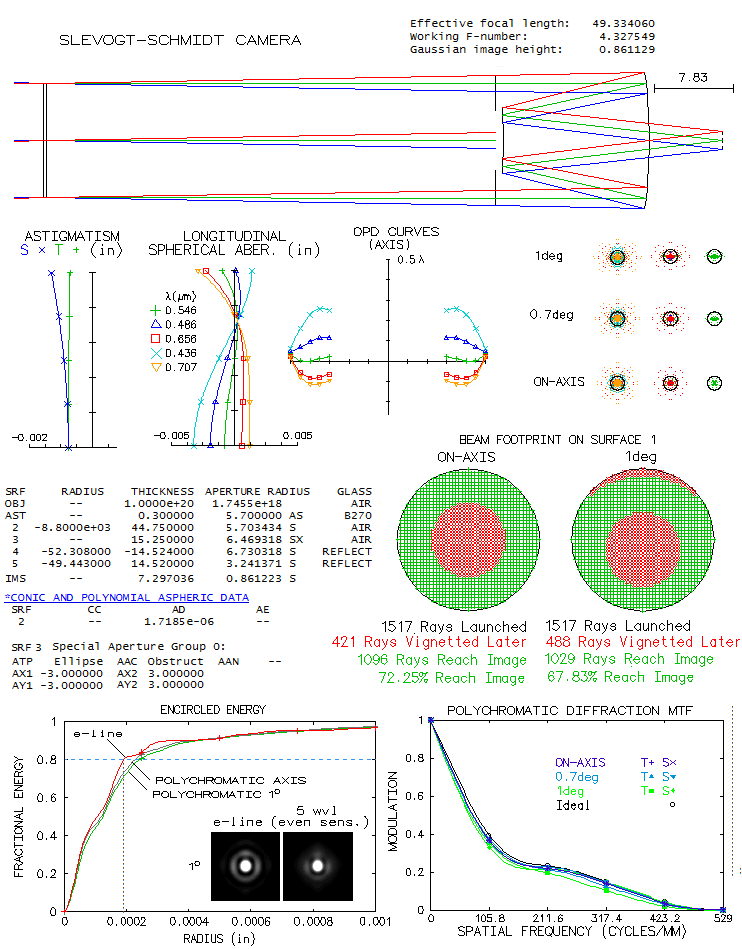

Raytrace shows excellent color correction, with as litle as 0.26/0.06

P-V/RMS wavefront error in the violet g-line. Astigmatism is very low,

reaching 0.22/0.05 P-V/RMS error 1° off axis on flat field;

central diffraction maxima is well defined all the way to the field edge. To

fully cover the 2° field the secondary would have to be 6.48 inch

in diameter, or 57% of the aperture diameter clear area only. Somewhat

smaller secondary would be acceptable: shown is vignetting with the

secondary clear area 6 inch in diameter: it is still only 6.1% at

1° off axis (circular red area is vignetting by the central

obstruction). Considering that the reduced central obstruction

would recover nearly 5% of light over entire field, including

edge, field illumination actually improved with smaller secondary.

Both, encircled energy plot and MTF show near-negligible drop to

the very edge of the field (note that polychromatic refers

to the five wavelengths plotted, for even sensitivity; it indicates

that the actual CCD performance is little better).

While given prescription indicates neutral zone near 0.707 radius

height, which generates over two times smaller wavefront error

than neutral zone at the 0.866 height, raytrace show that the latter

would have actually a slightly smaller 80% encircled energy radius.

This is due to the effect of large central obstruction, reshaping

the wavefront to practically cancel much larger error.

Still, the 0.707 neutral zone corrector is significantly easier

to make: its maximum depth at the neutral zone is 2.25 times smaller.

Note that the actual corrector here is with split profile, i.e.

each side gets half of it, but the effect is the same as with a

single side profile. Table below shows surface profile as the sag

values at each 1/16 inch of aperture radius. At right is exaggerated

profile with a quarter inch scale.

Would the image quality be better going with ρ=0.96 and m=1.8?

It would result in somewhat smaller secondary, but the back f.l.

would be reduced to 5 inch, with the RMS WFE 1° off axis

slightly higher. Extending back f.l. to 7.2 inches by placing

secondary closer to primary would change the value of k

and make best image surface slightly convex toward mirrors (R~2500),

only slightly worsening the RMS WFE 1° off axis (0.055 vs. 0.054).

Extending back f.l. by strengthening the secondary radius would

make best image surface concave toward mirrors (R=-166), with

the error 1° off axis cut in half on the best surface, but

increased to 0.15 wave RMS flat. Hence, when significantly

changing back f.l. determined by m~1.8 and ρ~0.96, using

equality m=ρ/(ρ-k), balk of the change in secondary

magnification should come from the change (increase for extending

back f.l.) in k, with the change in ρ only

needed to offset the induced field curvature. In other words, to make

β=(m+1)k-1 by 46% longer (7.3 vs. 5 inch), most of the

increase is to be contributed by a change in k.

Looking at the astigmatism aberration coefficient for flat

astigmatic field and using starting values ρ~0.96, m~1.8,

a simple relationship approximating the needed change in ρ

to compensate for the change in k is ρ'=0.99-0.07k'.

In this particular case, k changes from 0.425 to 0.444,

and ρ from 0.96 to 0.956 (minor adjustments to the

aspheric coefficients and radius term are also needed).

The above raytrace is design limit; the actual output will be

negatively affected by alignment errors and thermal imbalances.

Tolerance for the corector-to-primary separation is fairly

loose, with the error due to coma at 1° off axis increasing

from 0.05 to ~0.07 wave RMS with about an inch off (little more

away from, little less than inch toward primary). Error of 0.1" in

mirror separation induces ~0.2 wave P-V of spherical aberration.

Secondary decenter of 0.1mm up induces over one wave P-V of mainly

positive all-field coma, with that error more than doubling at 1° off

due to the image tilt. Secondary tilt of 0.1° counterclockwise

(top away from the primary) induces nearly

one wave P-V of negative all-field coma, along with somewhat more

than half as much of image tilt as the decenter. Since the secondary is spherical,

there is an offsetting combination of tilt and decenter; in this case,

offsetting tilt for the 0.1mm decenter is 0.116°, but the error

1° off axis would double due to the residual image tilt.

Built around 1998. this telescope of a renowned in ATM circles Dutch telescope

maker Rik Ter Horst, is a classical Kutter two-mirror tilted-components-telescope

(TCT) that instead of spherical uses toroidal secondary. It makes easier to

control aberrations of the two tilted mirrors, with the toroidal component

inducing mainly astigmatism. The system, as published on the Cloudy Nights

forum, consists of an ellipsoidal primary, little over half way between a sphere

and paraboloid, and a toroidal secondary (below; if the primary is left spherical,

the centerfield error is 0.022 wave RMS, mainly undercorrection, and if

paraboloidal 0.020 wave RMS of mainly overcorrection).

While Ter Horst describes sstem as free of coma and astigmatism, it applies only to the

central field. Farther off, they are both present, with astigmatism dominating. The

field of 0.25° is significantly larger than the intended field, as

indicated by the secondary cutting into the off axis light reflected from the primary,

but it is chosen to illustrate correction over full 2-inch barrel field. The intended

field is probably somewhat smaller than the 0.7 radius field here, closer to half the

radius shown (about 1/4-degree in diameter). The astigmatism plot shows the field edge

focusing nearly 3mm closer/farther than the central point (field top and bottom,

respectively, mainly due to image tilt).

If this image is looked at with naked eye, from the least distance of distinct vision

of ~25cm, the 3mm displacement of the top and bottom field point amounts to little over 1/100

of the distance change, causing practically identical relative change in the eye image location.

Assuming 17mm effective focal length of the eye, the top and bottom point will be imaged

~0.17mm closer, i.e. farther away than the central point. In diopters, the change amounts

to 1/0.01683 and 1/0.01717 vs. 1/0.017 for the central point, i.e. 59.42 and 58.24 vs.

58.82 for the central point, for about +/- 0.6 diopters accommodation. For all practical

purposes, it is as good as flat.

Over best image surface, ray spot plots vary somewhat in shape with radial orientation,

but diffraction images remain fairly similar for any given off axis distance, with the

central maxima remaining intact to the very edge. For the intended field, even the very edge

is better than the "diffraction limited" minimum (0.80 Strehl).

Image tilt creates asymmetrical ray geometry with respect to the eyepiece, hence always have

an effect on its output. As before, it is significant mainly toward top and bottom of the field.

Taking again a 50mm Plossl (scaled down version of the patented Nagler Plossl) to cover

the entire 2-inch barrel field, with a 17mm f.l. OSLO

"perfect lens" simulating the eye, the entire picture is scaled down as it is in the eye,

with the image still tilted, but with somewhat modified, asymmetric astigmatic field

(due to the asymmetric position of the eyepiece vs. image), creating a field curvature

element. Since the imaging element here is the eye, with 17mm effective focal length,

one diopter of accommodation corresponds to 0.29mm point displacement (from f2,

f being the f.l.). With the largest point displacement here of about 0.6mm for

the top field point,

required accommodation is about two diopters, i.e. the visual field is within easy accommodation

(since the top point requires extending converging beam, and the bottom shortening,

they cannot be focused at at the same time, and the latter, requiring lens contraction

is easier to the eye).

Note that it is important for the final image separation from "perfect lens" to be

17mm, because it is its designated focal length, hence this image separation indicates

that light pencils exiting eyepiece are collimated, i.e. that the eyepiece is properly

focused; even small deviations, a few 10ths of

a millimeter from 17mm image distance represent change in ray geometry that can result

in significantly different eyepiece aberrations.

Even when adjusted for tilt and field curvature, vertical field remains very

asymmetrical, with mainly low residual coma on the top, vs. significant astigmatism on

the bottom. Again, the diference diminishes significantly over the intended field, about

twice smaller. The common wisdom is that the definition improves with tilting eyepiece

to match image tilt (7.2° here), but things are not that simple. Tilting the eyepiece

to match image tilt makes it asymmetrically positioned vs. optical axis, and that also

have negative consequences. In this case, it greatly reduces astigmatism over entire

field, except the top portion (not within the intended field area), but at the same

time induces significant astigmatism (and a bit of coma) to the axial cone, which is now

shifted somewhat below

geometrical field center (bottom left, dashed line crossing). Exit pupil is also shifted significantly

below eyepiece axis, and is grossly distorted ("perfect lens" modifies cone geometry

in order to remain aberration-free, but the actual eye does not have that ability,

and would likely induce additional aberrations due to the exit pupil disarray). Half as

much tilt of the eyepiece does better overall job, reducing the bottom field astigmatism, with

about four times smaller error induced to the axial beam, and significantly smaller

exit pupil disarray (bottom right).

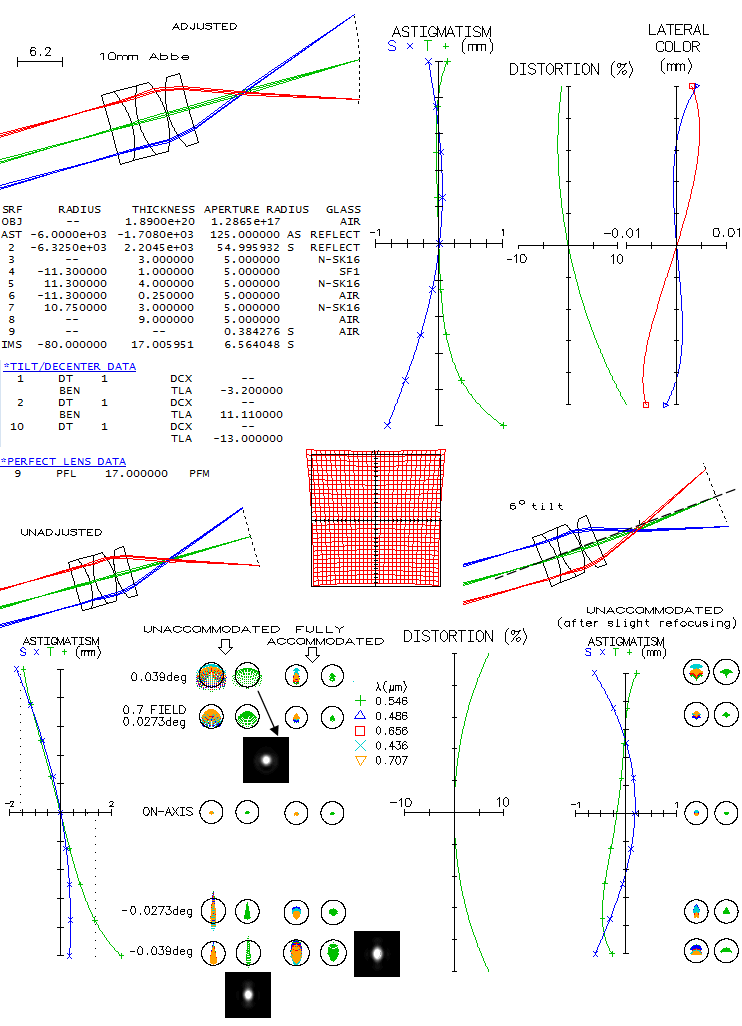

Going to shorter focal length eyepieces, for high magnifications, a 10mm Abbe orthoscopic with

~40° AFOV, when adjusted for image tilt and curvature (top) shows asymmetrical vertical field,

with significantl more of astigmatism toward field bottom. OSLO shows grossly asymmetrical

distortion as well, but it could be an artefact of field rotation. Lateral color is nearly

identical on both sides.

Here, the maximal point displacement from the plane determined by the

central point is about 1.5mm (bottom left), which translates to 5.2 diopters of accommodation -

pushing the limit for the average eye. The main displacement factor is image tilt, amounting to 13 degrees.

However, due to the tiny f/20 cones, even fully unaccommodated image is still well defined

even at the field top/bottom (0.088 and 0.079 wave RMS, respectively). Still, tilting eyepiece

to compensate for image tilt here further improves definition; a 6° tilt nearly evens up the

astigmatic field, removing tilt element. Exit pupil is somewhat decentered, but the axial cone

still nearly coincides with the field center. Longitudinal astigmatism generated in the field

center is nearly 0.4mm, but due to the tiny cone width - effectively ~f/35 in the perfect lens,

from the eyepiece exit pupil diameter 0.49mm and 17mm lens focal length -

it converts to only 1/15 wave P-V.

A few general notes about the design. This particular system uses secondary mirror somewhat

weaker than primary, probably to optimize the overall geometry for desired setup. Stronger

secondary would make the final image separation larger, hence it would need to be pulled

farther away from the primary, which in turn would enable use of larger unobstructed fields.

Stronger secondary, in general, generates more astigmatism which, being of opposite sign

of that generated by primary, results in a lower system astigmatism, and with the optimum

match the astigmatism can be practically eliminated, leaving only a slight residual coma (below).

The field is symmetrical, with the edge coma below the level of 1/8 wave P-V of spherical

aberration. The system is somewhat slower at f/24.6, due to the larger primary-to-secondary

separation, but the overall length is comparable. One negative of minimizing astigmatism is

nearly 50% larger image tilt, despite reduced tilt of both, primary and secondary. This is

partly compensated by the slower f-ratio. There is any intermediate combination of these

factors between the Rik Ter Horst's desing and this one, with gradually diminishing

astigmatism, increasing image tilt and focal ratio reduction. As indicated in the beginning,

designing with toroidal secondary is fairly easy. Since the final field is in effect superposition

of two aberrated fields, those of the primary and the secondary, partly compensating their aberrations,

appearance of center-field coma means that one of the two mirrors has relatively stronger

tilt than the other. Assuming that the primary tilt is given, positive center-field coma

indicates that the primary tilt is stronger than what it should be relative to that of the

secondary (inducing coma of

opposite sign) for cancelled center field coma, and it is simple matter of increasing

the secondary tilt until the center

field coma vanishes. Then center-field astigmatism can be brought to zero by adjucting the

toric value (with the toric in OSLO nomenclature given as the inverse of the toric radius),

which induces no appreciable coma. In the case of negative center field coma, secondary tilt

needs to be decreased.

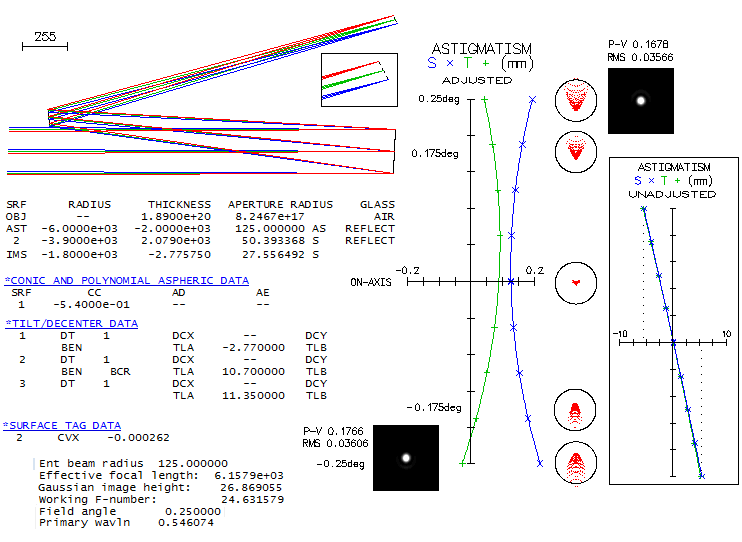

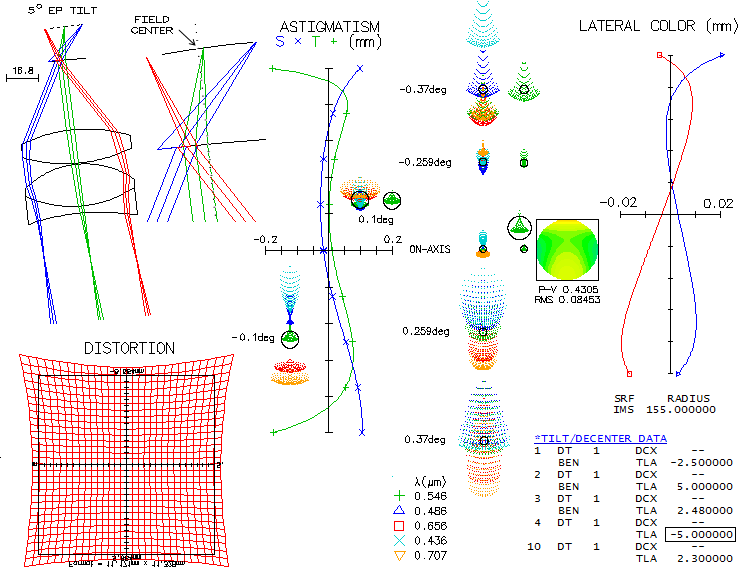

A work still in progress (as reported on the CloudyNights forum), this big aperture tilted

element telescope consists of the paraboloidal primary, convex spherical secondary and

concave spherical tertiary - the latter two of identical radius of curvature - with a flat

mirror added to make the final image accessible. The actual system may not be identical to

the published prescription, but differences should be negligible. System shown below is

raytraced for the full 2" eyepiece barrel field, in order to illustrate correction over full

field, but the actual design has field radius

limited to ~0.1° in order to minimize image tilt by keeping mirror tilt to a minimum

(field can be significantly larger

if a small and generally negligible grazing of the axial cone by the secondary is accepted).

Even with doing everything to minimize image tilt, it is still fairly hefty, at 9.9°

(toward the end, the system variant covering the full field without mirror obstruction,

with over 50% larger image tilt, will be analyzed).

Astigmatic plot for unadjusted field shows that the edge point displacement is 4.2mm for full

field, and 0.9mm for 0.1° field. If looked by naked eye from ~25cm, it represents 1.7% and

0.36% change in object distance vs. central point (respectively), hence will induce practically

identical change in the point image separation in the eye. In other words, the top full field point, being

farther away, will focus 1.7% of 17mm eye focal length closer, and the top full field point, being

closer, as much farther away. In diopters, it is (1/0.017)*0.017=1, which is practically as good as

flat. The field adjusted for tilt and mild curvature shows correction far beyond the treshold of undetectable

across entire field. Through an eyepiece, however, both eyepiece native aberrations and those caused

by the assymmetrically positioned field will significantly worsen correction level.

Starting with the full field, the corresponding conventional eyepiece would be of ~50mm focal length.

Taking Koenig 2+1, comparable in its correction level to Abbe and Plossl designs, shows that the

eyepiece image (it is actually image by the eye, in this case simulated by OSLO "perfect lens",

of more or less collimated light pencils exiting eyepiece), expectedly, suffers from significant

astigmatism assymmetry along the vertical field diameter. Top astigmatic plot shows field adjusted

for tilt and relatively weak field curvature, so that the top and bottom field point are near their

best focus. Since the astigmatism is a mixed lower and higher order, in addition to the imbalance, field

curvature is irregular and most of the rest of the field along its vertical diameter is not near its

best focus. However, the largest displacement from best focus is about 0.2mm (less than 0.7 diopters,

with one diopter with 17mm focal length being ~172/1000=0.29mm; alternately, 0.2/17 times 59

diopters for the effective eye focal length in diopters). In other words, when the adjusted field is

within the range of accommodation, the eye can see all its points at their best focus.

As mentioned, field curvature element is relatively

mild, and needed corrective tilt is 4.5 degrees. In the unadjusted field - the one that the eye actually

sees - it causes little over 0.8mm top point displacement,

and somewhat less for the bottom point (bottom astigmatism plot). Since the effective focal length of

the eye is 17mm, one diopter

of accommodation corresponds to 0.29mm, implying 2.8 diopters accommodation requirement for the top

point. With the horizontal field diameter essentially flat, it means that the entire field is

within comfortable accommodation for most people.

Field astigmatism can be better balanced by tilting eyepiece. In most cases the needed eyepiece tilt is roughly

half of the image tilt, in the direction of image tilt. Raytrace for 5° eyepiece tilt (below) shows

that to be the case, but at a

price of compromising some other image aspects.

Axial point is displaced from field center, with a better part of the field radius - including center -

being astigmatic, in excess of the diffraction limited minimum requirement (0.80 Strehl). The exit pupil

is in disarray, which likely generates additional eye aberrations.

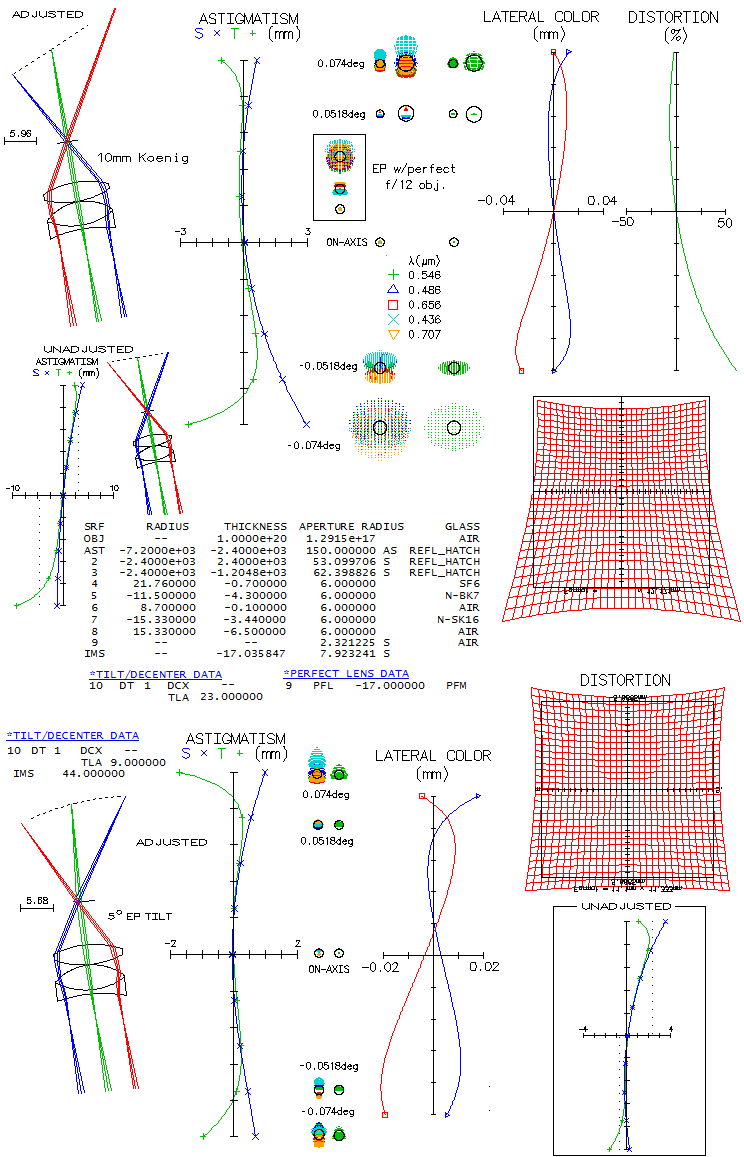

With a high-magnification eyepiece, like 10mm Koenig, and field size somewhat smaller than the intended

by design, the image field is again very unbalanced astigmatism-wise along the vertical field diameter,

with the only adjustment needed being in the tilt (top), as much as 23°. Unadjusted - i.e. actual -

field has the top field

point displaced by about 3mm, and the bottom one nearly 5mm, corresponding to over 10 and 16 diopters of

accommodation, respectively. Portion of the vertical field diameter within 5 diopters is roughly 1/2 on

the top side, and somewhat more on the bottom (due to the shape of astigmatic field). Lateral color is

somewhat assymmetrical, with the bottom vertical field radius having the blue/violet remaining overcorrected

to the edge. Also, distortion

becomes extraordinarily high.

Both, astigmatism and distortion can be nearly balanced by tilting eyepiece by about 5°.

Although some longitudinal astigmatism

is also induced to the central area (not noticeable due to its small magnitude and small image scale),

it is insignificant, more so

due to the very small f-ratio of the beam focused by the eye (i.e. "perfect lens"). Some lateral color

is induced to the axial point, but it is low enough to keep all five wavelengths safely within the Airy

disc. Here, unadjusted field - i.e. field formed on the retina - has the top point of the vertical field

radius displaced by about 2.3mm, and the bottom one by 0.8mm, i.e. nearly 8 and 2.7 diopters, respectively.

It places the top area of the field out of average accommodation range, but rest of the field is as shown

for the adjusted field at left.

As mentioned in the beginning, common wisdom with tilted elements telescopes is to keep tilt angles as

small as possible in order to minimize aberrations and image tilt (which itself becomes a source of

eyepiece aberrations). To illustrate how much it matters - or not - with this particular system,

here is raytrace of a system with these same elements and separations, only with tilt angles increased

so that a full 2-inch barrel eyepiece field can be accommodated. Designing is simple: tertiary mirror is tilted

as much as necessary to place the flat outside of the light path, and then the tilt of primary and secondary

is increased until the coma induced by tilting the tertiary is cancelled.

Adjusted field shows that despite significantly more of mirror tilt, correction remains practically

perfect. However, image tilt increased to 15.69°, with the top and bottom point of the vertical field

diameter displaced by 6.4mm, vs. 4.2mm with mirror tilt minimized. The effect of it on eyepiece image

is again evaluated using 50mm and 10mm f.l. units.

With the 50mm Koenig, the unadjusted field has top and bottom vertical field diameter points displaced

by little over 1mm, or nearly 4 diopters. Since this is within the accommodation ability of the average

eye, we can assume that the visual field will be about as corrected as the adjusted field (7.4° image

tilt and 800mm field radius). The consequence of larger image tilt is more of astigmatism imbalance along

the vertical field diameter: the top half is practically astigmatism-free, while at the bottom point

it is nearly twice as large as with a perfect 300mm f/12 objective. Lateral color error hasn't changed

significantly vs. smaller image tilt, but distortion is more out of balance, and significantly larger

overall.

With the 10mm Koenig, adjusting to image tilt takes as much as 33°, with an enormous distortion

imbalance. With unadjusted field, less than half of the vertical field diameter is within +/- 5 diopters

accommodation range, with roughly half of the remaining field being within some degree of partial

accommodation. Along the horizontal field diameter, correction is as with a perfect 300mm f/12 objective,

with zero tilt. This confines useable field within an ellipse with the top point at little less than 40%

of the top radius, bottom point at little over 40% of the bottom radius, and a full field diameter

horizontally (the effect of tilting eyepiece is omitted, but it is similar to that with the original

low-mirror-tilt system shown). Both, distortion and field restriction are larger than with the

unadjusted 10mm Koenig and

the original system, but not dramatically so. It suggests that there is little benefit from minimizing

mirror tilt with the Stevick-Paul design. While full 2-inch barrel field may not be necessary, there is

no reason not to have full field for 1.25-inch eyepiece barrel.

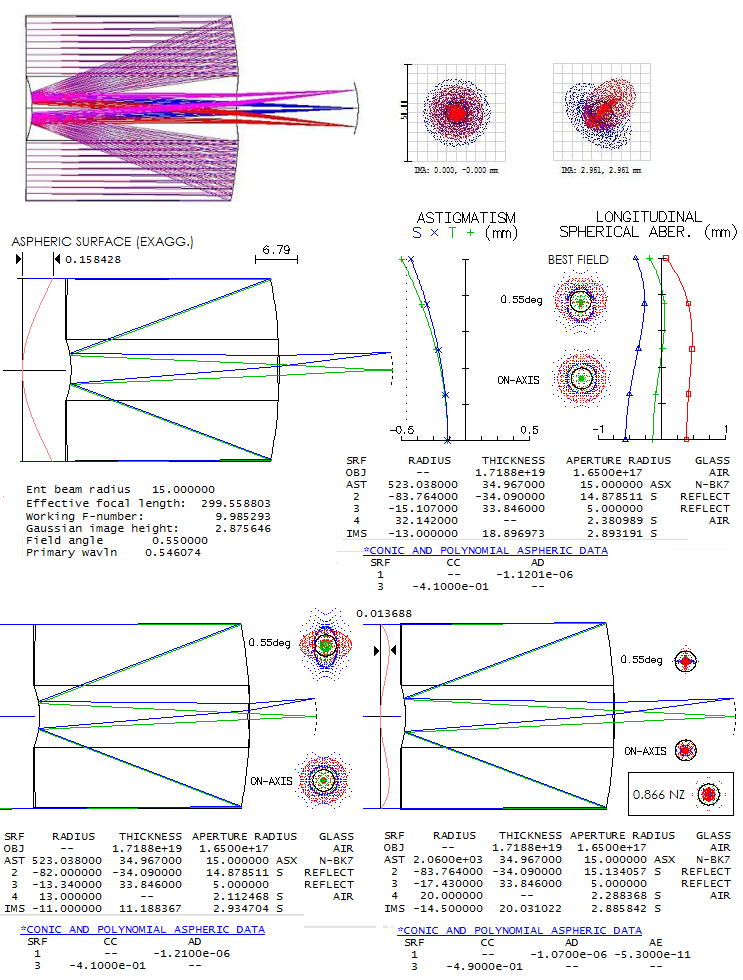

More than a decade ago, some details about this miniature SCT were posted by its creator on an astro forum.

It aroused a great deal of curiosity and admiration. Functional telescope made out of a single glass cylinder,

just large enough

to fit in the 1.25" eyepiece barrel. No prescription was published, but the system layout, as well as ray spot

plots were posted (below, top). The spots reveal significant longitudinal chromatism, lateral color error,

and relatively strong off axis astigmatism. The magnitude of these aberrations is unexpectedly large for

such a small aperture, making uncertain whether raytraced system was a design, or the actual system as it was

made.

Configuration nearly identical to the one posted achieves this magnitude of longitudinal chromatism only with a

very strong curve placed on the aspherized corrector surface (or, with the same effect, on the other side of the

corrector). There is no gain from having such a strong curve

neither with respect to fabrication, nor correction level. However, lateral color error is roughly half of that in

the published spots, and astigmatism not noticeable (the original off axis spots are given for corners of 4x4mm

field, hence they have a diagonal orientation). While the lateral color error can be increased by weakening the

rear end radius, it would further diminish astigmatism. On the other hand, achieving level of astigmatism

shown in the published ray spot plots would require significantly stronger rear end radius, which would cause

configuration to significantly differ from the one posted (bottom left). In other words, the ray spot plots

and layout published are not compatible. That indicates that the ray spot plots and the system

layout posted may have come from two different systems.

If fully optimized, such system would use aspheric profile with a 0.707 radius neutral zone, with the maximum depth

more than ten times smaller (13.7 vs. 158 microns, bottom right). Posted description states 21 micron deep aspheric

curve, which is closer to one with 0.866 radius neutral zone (just over 25 microns), but such profile would

produce significantly less of longitudinal chromatism (box above last prescription bottom right).

Note that only the fully optimized system (0.707 NZ) uses 6th order aspheric coefficient;

considering the magnitude of longitudinal chromatism,

the difference wouldn't be noticeable with the other two systems (but is noticeable with the axial spot for

the 0.866 NZ system, which only has the 4th order coefficient).

In conclusion, posted

material was probably showing the first prototype of this amazing little telescope, and some more or less related

raytracing material. If fully optimized, such system has impecable correction of all aberrations, except the very

strong field curvature. Edge vs. center displacement is about 0.45mm, which translates to 4.5 diopters of

accommodation (infinity to 0.22m) required with 10mm f.l. flat-field eyepiece, over a field radius less than half

the field of view of a standard eyepiece of this focal length. Since edge displacement is away from the eyepiece,

its pencil would exit it slightly converging, requiring unnatural accommodation by relaxing eye lens beyond its

infinity mode. That would probably make it unachievable for most people.

◄

14.1. Early telescopes

▐

14.3. Observatory telescopes

►

|